This is the first of three stories about a little-known geologic fault that could trigger a major earthquake in Snohomish and Island counties.

EVERETT — At a downtown coffee shop, the mugs begin to chatter.

Small talk stops. There’s an uneasy hush. A barista’s hand hovers over the bean grinder. Customers lift their eyes from phone screens.

Then the world rattles up and down. Dishes jitter off tables, shattering on the floor. Someone screams. Seconds later, it’s as if Everett is trapped in a cocktail shaker, lurching back and forth.

Brick chimneys cascade off rooftops. Bookcases and china cabinets topple, trapping people beneath. Disoriented drivers wonder what’s wrong with their cars, then realize something much bigger is amiss.

In the Snohomish River delta, sandy soil wobbles like Jell-O. Older buildings tilt and sink as if in quicksand. Water bubbles through widening cracks in the asphalt of U.S. 2. The trestle whips and snaps into pieces. Cars are stranded on islands of highway.

Facades crumble off buildings along Hewitt Avenue, and some of the oldest structures collapse in a roaring cloud of dust. People stagger into the streets to avoid an avalanche of debris. Standing becomes almost impossible as the jolts turn to rolling waves.

Around Puget Sound, it seems everyone knows about “The Big One,” the potential magnitude 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake some scientists say is due any day.

But this isn’t it.

This earthquake is along the southern Whidbey Island fault, a less-known, less-studied subterranean boundary. And for Snohomish County, experts fear it could be even worse than “The Big One.”

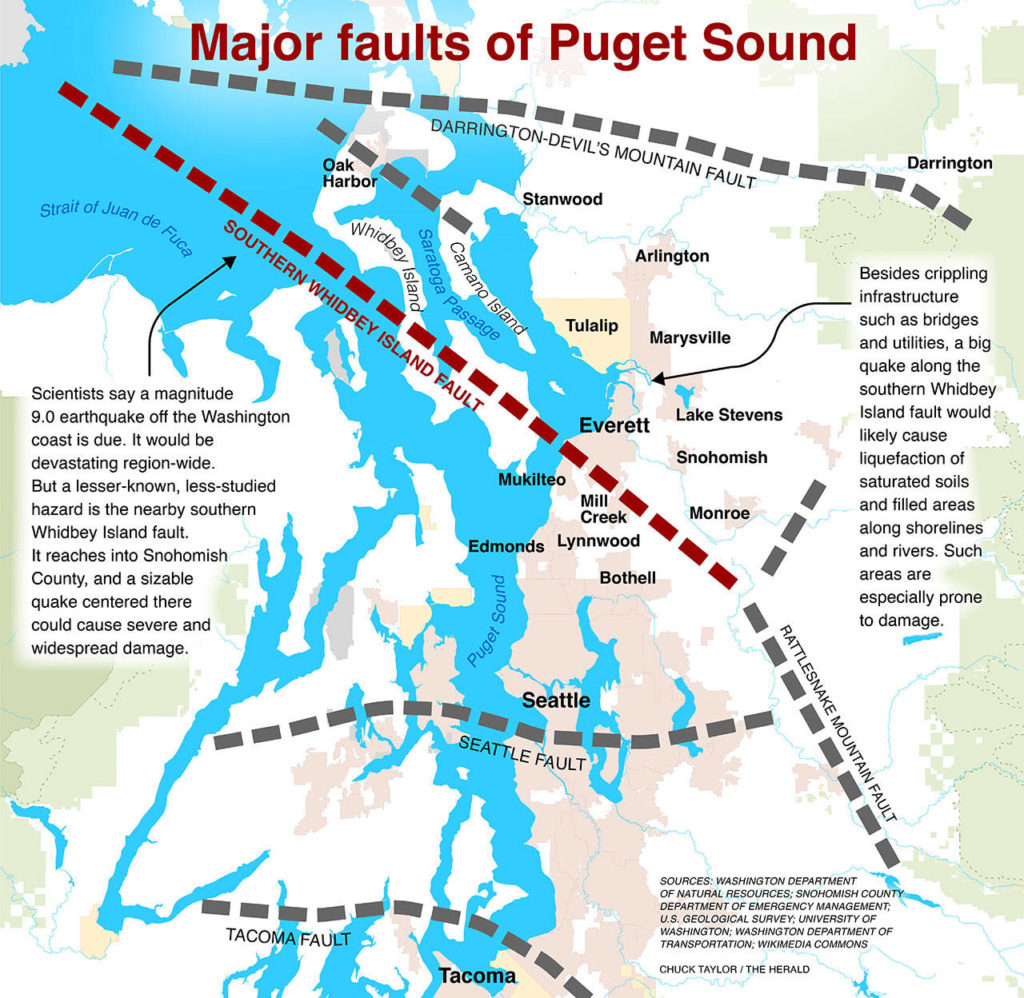

The fault zone, known to geologists as SWIF, cuts through Puget Sound in a diagonal line roughly from Port Townsend to the southern tip of Whidbey Island, then to Mukilteo, Bothell, North Bend and possibly farther east below the Cascades.

Consider a magnitude 7.4 quake with Everett at or near the epicenter.

Under a scenario played out in a 2019 U.S. Department of Homeland Security study, about 80% of state-maintained bridges in Snohomish County would be severely damaged, leaving them unusable for months or years.

Over 10,000 buildings could sustain extensive damage.

Power could be out for days.

Restoring tap water to homes could take over a year.

Almost 5,000 residents would lose housing temporarily or permanently.

Hundreds could die, with thousands more injured.

This is the hypothetical scenario created by Mark Murphy of the Snohomish County Department of Emergency Management. In 2017, he began studying the possible aftermath of a major SWIF quake. He combed through state and federal data to understand the risk in Snohomish County, and to help train first responders.

The threat to Puget Sound from a quake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, off the coast of Washington, Oregon and California, is well documented. Experts believe a magnitude 9.0 could happen there anytime in the next 200 years or so.

Despite its location well offshore, a Cascadia quake would likely kill at least 10,000 and injure more than 30,000 in Washington, Murphy found. The same data predicted three deaths and 150 injuries in Snohomish County.

A major southern Whidbey quake, on the other hand, could kill as many as 340 and injure 5,000 more here, according to Murphy’s estimate. Unlike The Big One, scientists who have studied the southern Whidbey fault have a far less clear understanding of when the next sudden shift might hit.

The quake, Murphy said, “is probably the worst thing that could happen to the county.”

Until the 1980s, no one knew SWIF existed. Until much more recently, no one really understood what it could do to a region of over 4 million people.

A cryptic fault

A pair of scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey first theorized that a fissure between two major blocks of the Earth’s crust might run through this slice of Puget Sound. Years ago, Howard Gower and James Yount came to the Puget lowlands to study earthquake risks and stumbled on what appeared to be a fault in Island and Snohomish counties.

In 1985, with little concrete evidence of its existence, the pair included the possible fault on a geologic map published by the USGS.

They didn’t recognize the significance of what they found.

“They knew something was there,” said Sam Johnson, a retired USGS geologist who would follow up on their work. “But they didn’t document it hardly at all.”

So the fault remained mostly a mystery until the 1990s. Johnson, on a whim, acquired the data that would prove its existence beyond a doubt.

At the time, Johnson worked in southwest Washington, searching for natural gas and oil deposits. In the late 1960s, speculators considered the Puget Sound region a frontier for petroleum exploration. Oil companies descended in search of riches. Finding nothing of serious monetary value, the companies abandoned reams of information they had gathered through seismic surveys.

Years later, that data proved priceless.

“It might as well have been sitting in a drawer,” Johnson said.

Though it was not directly related to Johnson’s work, he asked a friend working for Mobil Oil to pass along the information. The friend obliged.

“It’s just the way scientists work,” he said. “If they know there’s data available that could help them in any way, they want to get it. It’s a natural curiosity.”

Johnson’s curiosity changed the course of his career.

The seismic mapping had cost millions of dollars — far beyond what most geologists on a government budget could scrape together.

Like a sonogram, the seismic surveys allowed Johnson to see outlines of massive fissures in the Earth’s crust. Within minutes, he spotted something groundbreaking.

“Once we got it, we were sort of shocked to see these big faults in the Puget lowlands,” he said.

The southern Whidbey Island fault, and several others, were exposed for the first time from a camouflage of forest, ocean and glacial sediment. It startled Johnson that such massive faults had gone undetected for so long.

Not all faults are active. But the mapping offered geological clues that the newly found fault was indeed capable of future quakes.

In the early 2000s, USGS scientists including Brian Sherrod set out to further Johnson’s work and better understand the slumbering fissure. The key, Sherrod’s group would discover, was buried on Whidbey Island under layers of mud, peat moss and decaying marsh grass in the murky tidal waters at Crockett Lake, alongside the Coupeville ferry dock.

Sherrod remembers his son, 5 years old at the time, playing with toy trucks on the mossy banks of the marsh while the scientists worked. The years have gone by. Sherrod’s son has since completed graduate school in applied geosciences.

On a frigid, blustery day in December 2018, Sherrod revisited the site where he conducted much of his field work.

His team wanted to find the rate of sea level rise along the shore. An abrupt rise or decline in sea level would reveal if the fault had triggered a quake before.

By sampling sediment from the marsh to the beach berm, Sherrod and his research partner, Harvey Kelsey, developed a timeline of the ocean’s climb.

A few miles southeast across the white-capped waves of Admiralty Bay, Lake Hancock rises and falls with the tides. On an inactive fault, the sea would have risen at the same rate at both locations. But it didn’t. The marshy deposits are about a meter higher at Lake Hancock.

“Everything points to one thing,” Sherrod said, waving his hand across the inland sea. “This is an active fault.”

The evidence shows each lake rests on different free-floating jigsaw pieces of planetary crust, separated by the southern Whidbey Island fault. The height difference likely was caused by a 7.5 magnitude earthquake on the fault about 2,700 years ago, Sherrod said. He believes dramatic shifts from that quake also may be visible on the western edge of Camano Island.

Along the water at Cama Beach State Park, cabins on a bluff overlook Saratoga Passage, facing the general direction of Lake Hancock on the other island. The southern Whidbey Island fault divides the two. The bluff, where the cabins now sit, could have jutted up in the most recent Whidbey fault quake, Sherrod said.

At the Brightwater treatment plant in Woodinville and at Crystal Lake in Maltby, the government researchers found telltale slopes of offset ground, known as scarps, indicative of a long-ago quake.

In the Puget Sound region, it takes a trained eye to recognize rocky outcrops and subtly raised ground as evidence of a fault. One of the best views of SWIF should be from Grand Avenue Park in Everett.

On a brilliant November day, Sherrod took in the panorama from the park’s bluff. Each peak of the Olympics stuck out with picturesque clarity in the distance. The fault, not so much.

“Here, we’re looking at one of the bigger faults in the region,” he said. “And what we’re looking at is water.”

The southern Whidbey fault is unlike more visible faults on the West Coast. The San Andreas in California, for example, left gaping scars in the Earth’s crust, at the surface.

SWIF ranges from 12 miles underground at its deepest to right at sea level in a few scattered spots, like Cama Beach, Holmes Harbor and Woodinville, according to Sherrod’s research. The fault has at least three almost parallel strands within a 4- to 7-mile-wide band, stretching eastward from Vancouver Island.

Scientists are not sure how far east it goes. One model suggests it extends to about 30 miles east of Yakima. The fault’s length depends on whom you ask, Sherrod said.

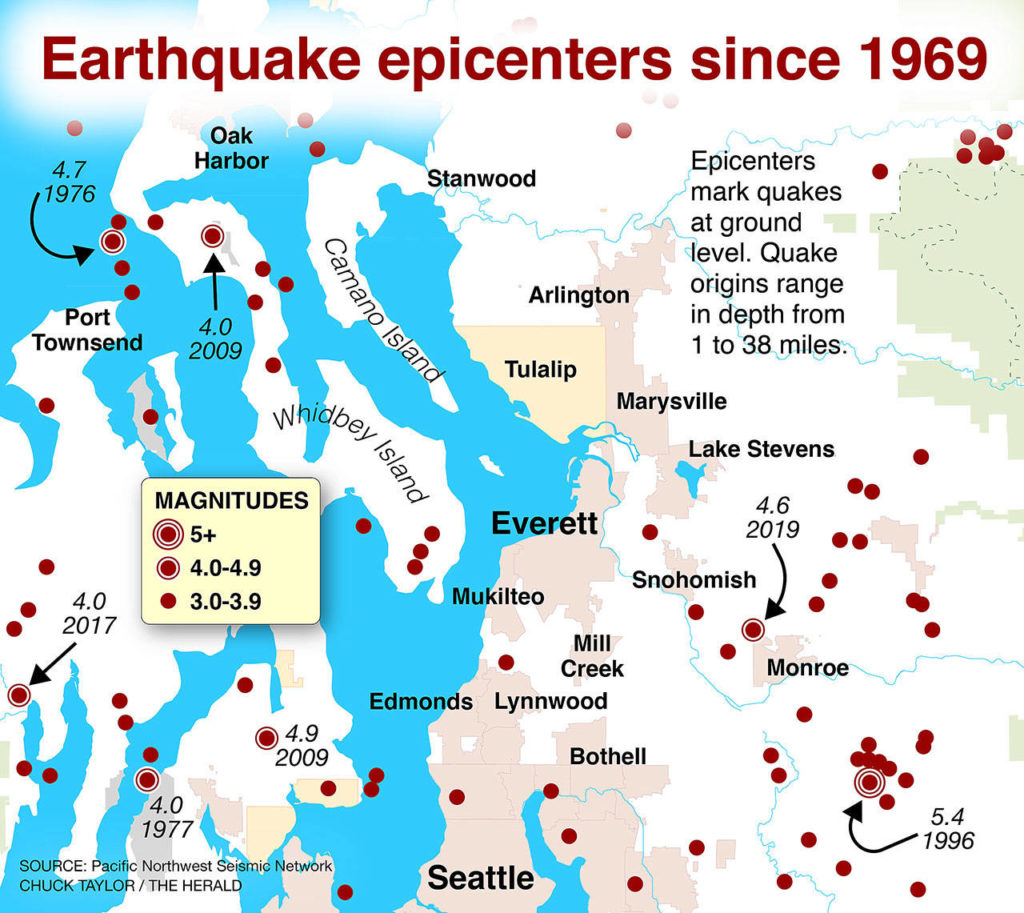

During site visits in 2005, Sherrod’s team found evidence of four SWIF earthquakes in the past 30,000 years. The most recent hit roughly 2,700 years ago.

So when will the next one erupt?

Sherrod shrugged his shoulders. Scientists don’t know. They haven’t dug up enough history to estimate.

“I wish we did,” he said.

The other big one

In Washington, there are three kinds of quakes.

One is caused by an oceanic plate diving under a continental plate. That’s what will eventually happen in the Cascadia Subduction Zone. A megaquake there erupts every 250 to 1,000 years, and the most recent hit in 1700. So it could be due. That’s what everyone calls The Big One.

A second type is a deep event, originating on a crustal fault about 30 miles or more below the surface, like the 2001 Nisqually earthquake that was felt as far away as Salt Lake City.

Then there are quakes on shallow faults in the crust, like the southern Whidbey Island fault and the Seattle fault, a similar fissure that runs under Bainbridge Island east to Seattle and roughly follows the path of I-90. Because those ruptures are so close to the surface, they can produce much stronger shaking than a deeper, crustal fault or the subduction zone offshore.

The shallow faults pack the potential to be the real “big ones” for Puget Sound, U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Erin Wirth said.

A magnitude 7.4 along the southern Whidbey fault would rattle 18 counties in Washington, according to a federal projection.

Snohomish, King and Island counties would be expected to see the most most deaths, injuries and property damage.

Scientists still have many questions about the recently discovered fault.

Just how far east does it stretch?

Will it cause a tsunami?

A Cascadia Subduction Zone quake could send a series of waves up to 30 feet high hurtling toward the West Coast and charging across the Pacific Ocean to Alaska, Hawaii and Asia, according to the Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup, a nonprofit collective working to improve earthquake preparedness.

But for SWIF, a tsunami depends on what kind of motion the fault makes when it ruptures, Sherrod said. If it’s a vertical snap, rather than a side-to-side scoot, it could produce a ripple of waves like a stone tossed into a pond.

The U.S. Department of Natural Resources built models based on a magnitude 7.3 earthquake from the Seattle fault. If that fault ruptures, the resulting wave could submerge parts of the Everett waterfront, Hat Island, the Snohomish River delta and much of Jetty Island. The waves would reach the Everett waterfront within 25 minutes, sending water across Naval Station Everett and east to Marine View Drive.

[Local earthquakes: Where to learn more and how to prepare]

Waves could produce a massive rip current rushing 9 to 16 mph in constricted waterways, like those between Everett’s shoreline and Jetty Island and in the lower reaches of the Snohomish River.

Sand deposits from tsunamis have been found in the lower Snohomish River near Spencer Island in Everett, coinciding with known earthquake activity along the Seattle fault.

The Tulalip Tribes tell a story of a great wave and a landslide in the 1820s or 1830s on southern Camano Island, at a spot known as Camano Head. That tsunami drowned people digging clams on nearby Hat Island, according to the tribes. Their 2010 emergency plan states that “the Tulalip Tribes consider this event a very tragic moment in their history and accordingly consider tsunami a major hazard.”

Scientists know even less about the southern Whidbey fault than the other shallow fault used in local tsunami projections. But the more researchers like Sherrod learn, the better Snohomish County residents can plan for what could be one of the worst quakes to throttle Puget Sound in over 3,000 years.

“The more we know, the more we can mitigate,” Sherrod said. “If we know where these things are and how big the earthquake will be, we can actually build for them and take them into account.”

The region will likely need a year to clear debris before rebuilding can begin in earnest, according to county officials. But it won’t be total annihilation.

“There’s pockets of damage,” Sherrod said. “Everything is not completely destroyed.”

The earth quiets

The shaking lasts 47 seconds.

When the ground stills, people crawl out from under desks. They dust themselves off and begin to survey the damage. Some race to high ground, not knowing if a tsunami charges toward them. Within minutes, blaring sirens, radio broadcasts or cellphone alerts may warn of a potential surge.

Many mistake it for The Big One, the 9.0 Cascadia quake. They dig into pockets and purses for their phones. A massive surge of calls crashes the cellphone networks. Some texts make it through.

Almost immediately, Twitter floods with images of a 7.4-magnitude quake.

Cellphone coverage is spotty, so amateur radio operators become critical for reporting injuries and damage to the county Department of Emergency Management.

Piece by piece, we get a picture of the true extent of the quake’s severity, as weakened buildings cave and aftershocks pummel a shattered community.

Julia-Grace Sanders: @Sanders_Julia on Twitter

Read the rest of this series

1. Buried danger: A slumbering geologic fault beneath us

An earthquake along the southern Whidbey Island fault reshaped the land some 2,700 years ago. Another big one is expected, and it could be devastating. THIS STORY

2. Built on pudding: Can modern quake engineering prevail?

At least 30,000 people in Snohomish County live on saturated soils and sediment that will behave like shaken liquid when a big earthquake hits. READ MORE

3. Aftermath: Infrastructure won’t fare well in a big quake

Shockwaves from a shallow fault here could ravage bridges, schools and the water supply in Western Washington. Emergency planners want you to be ready. READ MORE

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.