SNOHOMISH — As the heat faded that summer evening, a Gold Bar man and his girlfriend strolled to the rocky riverbank and waved at the rafters gliding down the Skykomish.

A woman in a one-piece swimsuit stumbled over boulders, in a daze, to the man’s backyard. She asked where she was and if she could walk to town along the river. It was around 6 p.m. on July 28, 2019. The man was not sure what to think. Was she high on something? The couple told her the only way out was to keep floating downriver or to hike out with them, through the neighborhood.

“Are you OK?” he asked the stranger. “You’re bleeding.”

A red streak as wide as a finger flowed from her nose, but Jamie Gonzales had not noticed. She told the man she was fine. In reality, she later said, she was in shock, ashamed and reluctant to say what her partner had done to her.

Jeremy Pidgeon, a martial arts trainer and high school wrestling coach, had beaten her in an inflatable raft on the river. Later, she told a jury he hit her head with the butt of a hard plastic paddle until she saw black spots and collapsed into the water.

The Gold Bar man called 911 while the women talked.

“Honey,” the woman said, according to Jamie Gonzales, “do you want to die next time?”

Jamie Gonzales did not know the woman’s name. She still doesn’t.

“Aren’t you tired of this?” she continued. “Do you have kids?”

“Yeah, I have kids,” Jamie Gonzales replied.

“What are you doing to them?”

For the mother and her two daughters, it was a turning point in their lives.

“It was just kind of like our saving grace, honestly,” Jamie Gonzales said. “I don’t know if we would still be there.”

Pidgeon was arrested. A Snohomish County jury convicted him of domestic violence assault in the fourth degree in May. He lost his job as the head girls wrestling coach at Snohomish High School, but he has continued to advertise self-defense classes for women, kids and law enforcement at his gym, Team Mean in Snohomish.

Through his attorney, Jeremy Pidgeon declined an interview for this story, and he declined to respond to specific allegations made by his former partner and kids.

Jamie Gonzales wants other domestic violence survivors to know some things that took her a long time to realize.

There is a way out.

There is light on the other side.

And abuse can happen to anyone, even the strongest among us.

Jamie Gonzales holds a blackbelt in kickboxing. Her daughter, Joessie, won a state wrestling title in 2018. Her youngest child, Alycia, is a kickboxer and wrestler who narrowly missed a roster spot on the U.S.A. Wrestling Cadet World Team in 2019.

“We want other people to know it’s OK to reach out,” Joessie Gonzales said. “It happens to people who train in a sport to defend yourself. It happens to people who are doing great things but are just unable to talk about it.”

The first time her partner assaulted her, Jamie Gonzales was pregnant with Alycia, she said. They were arguing, she said, about how he had been partying for two nights in a row. She wanted to go to her mom’s house for the evening, and when she tried to leave, he kicked her in the face, she said.

“So I didn’t go to my mom’s, I wound up staying there,” Jamie Gonzales said in an interview, “because I thought, ‘Well, what is everyone going to think? I can’t tell nobody. Like, I’m OK, and he won’t do it again.’ And he didn’t hit me again, for a while.”

In court last month, Alycia Pidgeon told a judge her father was known as a “man of light in the community.” Yet her mother and both of the sisters endured abuse at home for as long as she could remember, she said.

“And how old are you?” District Court Judge Patricia Lyon asked.

“I’m 18 years old.”

Team Mean

In his prime, Jeremy Pidgeon was a limber welterweight, 170 pounds, who fought in mixed martial arts. He had wrestled in high school in Everett, and he never lost a pro bout.

He stocked fruit and vegetables in his day job at Albertsons. Jamie Gonzales cut meat in the deli. In their 20s, they dated for a couple of years, then moved in together. He already had a son. She had a daughter.

“We were pretty young,” said the mother, now 41. “And so he was still kind of partying and doing drugs. And I was like, ‘Oh man, we’re about to have a baby.’”

Jeremy Pidgeon, 43, fought as an amateur and a pro in mixed martial arts in the early 2000s. He had what fighters call “heavy hands,” his former partner said.

In a polished promotional video, still featured on Team Mean’s website as of this month, Jamie Gonzales tells the story of how she fell in love with kickboxing. She’d just had her second child and wanted to get in shape, but she was nervous.

“For women, this is a definitely a great thing to do,” she says in the video. “… When I got in there, and I actually did it, it was probably one of the best things I ever did for myself.”

They trained at Charlie’s Combat Club in Everett before branching off, about a decade ago, to start their own gym on Bickford Avenue. Often, bruises from domestic abuse would be explained away as injuries from a fight, Jamie Gonzales said. If her partner had a bad day, she said, he would go hard on her or one of the girls while sparring.

“I would know I did something wrong because he’d be like, ‘We’re going to spar,’” she recalled. “Unfortunately, that gym was a lot of the coverup. Like, if we did something ‘wrong,’ he wanted to do rounds with us. Everyone’s in there doing rounds, and they just thought, ‘Oh, he’s trying to toughen us up,’ but we’re falling to a knee.”

Once, as Jamie Gonzales trained for a scheduled fight, he kneed her so hard she felt something crack in her chest. She went to a doctor. Two of her ribs were broken, she said. She had a black eye, too. She told the doctor it was from training. That part was true, and the bruise likely came from a different fight, she recalled. She stopped fighting official matches about five years ago. She sparred less. Bruises made less sense.

Jamie Gonzales turned on her cell phone camera on June 24, 2018, as her then-partner drove down Bickford. Jeremy Pidgeon had been drinking that day, she said. They were waiting at a stop light by the Fred Meyer. The lens shows little more than a blur, but the audio recording captured an argument about Jamie Gonzales’ father, who had just been diagnosed with a mental illness.

“It’s an inconvenience, I get it,” he says. “It’s an inconvenience to your mom. It’s not inconvenient when he’s (expletive) working and paying the bills. It’s inconvenient when he can’t do any of that.”

“Whatever, Jeremy,” she says. “You didn’t try to help at all, so be quiet.”

“I was there!”

“You were there for what? How many times did you see him when he was sick?”

Suddenly there’s a loud smack, the sound of a fist bashing into teeth.

“You want to (expletive) with me, (expletive)?” he says.

Jamie Gonzales moans, then screams, then begs for Pidgeon to pull over. He kept driving home, she recalled.

The force of the punch left obvious dark marks on her chin, visible for over a week, she said. She could hardly eat while it healed.

The abuse came in bursts, according to Jamie Gonzales. Sometimes her partner would not hit her for a couple of years. Sometimes, she said, there were five “big” incidents in a year. It grew worse in the last three years of the relationship, she said.

“I’m not saying that he’s out to kill us,” Jamie Gonzales said. “But do I watch my back? Most definitely. Most definitely.”

‘Living his dream’

Alycia Pidgeon was about 5 years old when she slipped on a metal grate at a dock. It cut her knee and left a scar. Her dad was so mad at her crying, Alycia said, that he picked her up and told her: “If you don’t stop (expletive) crying, I’m gonna slit your throat and drown you in the lake.”

Gonzales and her daughters each experienced a different kind of abuse, according to their accounts. All three said they witnessed how the others suffered.

As she grew up, Alycia’s father punished her for showing emotion, she said. After a devastating loss in a finals match in her sophomore year, she hyperventilated in a back room. Her sister tried to comfort her.

“And (Jeremy Pidgeon) was so mad, he just upper-cutted me to the stomach,” Alycia said.

Her father tried to justify it, she said, by saying he thought it would help her to catch her breath. Other kids saw it, Jamie Gonzales said. Nobody reported it at the time.

“We were just so used to it happening that we didn’t feel the need to reach out,” Joessie Gonzales said.

Other times, when they were hidden by bleachers, the coach slapped his daughter Alycia in the face hard enough to leave an imprint, she said. At least once, there were witnesses outside the family, the women said.

“There was this little boy just, like, staring at her in the stands from above, and he even asked you if you were OK,” Jamie Gonzales said to Alycia during a group interview last month. “I just thought to myself, a little kid that’s 6 years old knows something’s not right there.”

Alycia said he often called her fat.

Joessie said he often called her stupid.

Those insults were often laced with expletives.

Jeremy Pidgeon never hit Joessie Gonzales outside the ring, but she avoided sparring with him. Even when she was hurting, and needed him to ease up, he would keep punching her hard, she said. That doesn’t happen in her new gym, Joessie Gonzales said. The psychological abuse was real, too, and she’s still dealing with it, she said. She thought maybe if she found success on the mat — winning All Districts or Regionals, or doing well in national competitions, or achieving the ultimate goal of a state title — that it would stop.

There’s a dramatic photo of Joessie Gonzales that ran in The Daily Herald in February 2018, the featured image with an article about the successes of Snohomish County girls who wrestled at Mat Classic XXX. Joessie, in a red singlet, looks to be sprinting off the mat. She’s bursting with emotion, on the verge of tears, still wearing a mouthguard, as she celebrates victory in the 130-pound weight class. Her coach, Jeremy Pidgeon, is quoted explaining how she pushed herself so hard in the match, in spite of what he suspected was an Achilles tear.

“He was living his dream through me at that point,” Joessie Gonzales said. “And so when I finally won state, I was like, OK. It was a relief. One, it’s my goal, because I do love wrestling. At the same time, I was like, OK, he’s not going to be on my back as much, because I achieved his goal — even though it was my goal.”

Demeaning comments didn’t stop, she said. Once she left home for Southern Oregon University, she came to understand the way her family lived was not normal or healthy, she said.

“Your mentality is a lot different when you’re in a survival situation,” Joessie Gonzales said. “You don’t realize how much it affects you.”

Reminiscing with her sister on a living room couch, Joessie Gonzales said she felt the others had it worse. At least she didn’t get hit. Alycia Pidgeon stopped her.

“Comparing your trauma with someone else’s — it’s still trauma, like, you can still speak out on it,” Alycia said.

You can drown in 3 feet of water, or you can drown in 20 feet of water, she said. Either way, you die.

‘Saving grace’

It was a picture perfect day to float the Skykomish: sunny, 80 degrees, the river low and mostly lazy, with pockets of swift current.

A week before July 28, 2019, Jeremy Pidgeon had been caught being unfaithful to his partner, according to his testimony in court. She found out via social media. Before they set out on the boat, he asked her if she was going to leave him when the kids got older. She seemed unhappy with him and standoffish, he testified.

The couple shared a two-seat inflatable raft. Some of Jeremy Pidgeon’s friends floated with them in separate rafts. He was drinking hard ciders from a cooler built into the boat. Jamie Gonzales had wine earlier in the day, but didn’t drink on the river, she said. She felt tired. Their raft kept bleeding air, so they fell far behind the group. A few times they pulled over to refill air. They didn’t have a pump. So they used their lungs.

Jeremy Pidgeon insisted to his partner that the others gave him a bad raft. According to Jamie Gonzales, she told him to calm down, because they would make it down the river, even if it took longer. That angered him, she said: He told her of course she didn’t care, because she didn’t buy the raft.

The Sky River bends off 172nd Street SE, and the current eases. The water might be 40 yards from shore to shore in late July. It runs beside a much wider channel of dry riverbed, where the rocks can be 8 feet tall.

“I should’ve gotten rid of you and the kids a long time ago,” Jeremy Pidgeon said, according to his former partner.

She recalled turning away and muttering, “God, is this really what you want for me?”

“God?” he replied, according to Jamie Gonzales. “There is no God, God can’t save you.”

He swung at her with a paddle in his hand, Jamie Gonzales said. She shut her eyes. She grabbed her face, stunned, and leaned forward. He hit her again in the back of the ear, she said. She was “rocked,” she said. She saw spots. He hit her a couple more times, she said. She fell into the current.

“Good riddance,” he told her, according to Jamie Gonzales.

She has been hit hard before in fights. She believes her training kept her from totally losing composure, and she soon found the river was shallow enough to stand.

“My legs were not underneath me at all,” she said. “They were so weak and shaky. … I remember telling myself, ‘If this is it, this is it, I’m out, I can’t go back.’”

She staggered to shore, unaware she still had a bag tied to her, with her keys, wallet, her phone and her partner’s phone. She saw the people on the shore. The Gold Bar man testified the stranger looked confused: She asked bizarre questions, looked to be all alone, wandered off, then came back. Her overriding fear, Jamie Gonzales recounted, was that she didn’t want her partner to get in trouble.

“It’s sick to say it, but I was more worried about Jeremy’s reputation, and what he could lose, because he had so much,” she recalled. “Would I do that again? No. Never again.”

Jamie Gonzales felt cold. The couple wrapped a blanket around her, then waited for the police.

“OK, well, this is your ticket, honey,” the woman said. “This is where you get to tell your story and you’re free.”

‘All my past fears’

Snohomish County sheriff’s deputies could not track down Jeremy Pidgeon that night. He was arrested July 30, 2019, in Snohomish. A sheriff’s sergeant noted he had no obvious injuries, aside from the ears of a longtime boxer.

Two weeks later, Jeremy Pidgeon posted on Facebook.

“Calling all LADIES,” he wrote Aug. 12, 2019. “The whole month of September LADIES train FREE !! NEW customers only limited spots available.”

He continued to advertise self-defense training for kids, as well as free training for law enforcement, over the past two years.

Snohomish School District spokeswoman Kristin Foley confirmed Pidgeon coached at the high school from 2014 to 2019. She declined to release further information about why he lost his position, saying it was a personnel matter. She also declined to say if he was investigated for misconduct by the district.

The criminal case was delayed almost two years, in part due to the pandemic. Meanwhile, wrestling friends converted a garage into a living space for the mother and her daughters, who fled their former home without packing on the night of the assault.

Some people reached out in support. Others told Jamie Gonzales that she brainwashed her girls against their father, who was well known as a coach and trainer. She learned many lessons about why survivors of abuse don’t speak up. There’s the disbelief of friends, even loved ones, who did not see violence with their own eyes; the snail-like pace of the justice system; the fear of being picked apart on a witness stand; the fear of sitting in front of a jury, to tell strangers your darkest memories; and the fear of being in a room across from a person who hurt you so much.

“You’re already beat down because you’ve been abused,” Jamie Gonzales said, “and then they want you to stand up to your monster.”

Attorney John Garza focused the defense’s case on the accusation that Jeremy Pidgeon “viciously beat Ms. Gonzales with the butt of a paddle.”

“That is the specific allegation Mr. Pidgeon has been motivated by, this entire trial proceeding — this entire case — to push back against, your honor,” Garza said in court.

An evidence photo of Jamie Gonzales’ face, taken minutes after the beating, suggested the altercation was not as severe as the victim claimed, Garza told the jury.

“I said from the beginning, this is a picture that proves Jeremy Pidgeon is innocent,” Garza said in his closing argument.

Deputy prosecutor J. Patrick Patterson pointed out it takes time for bruises to show up.

On the witness stand, Jeremy Pidgeon did not deny forcing his partner to fall out of the raft. He claimed he made a comment that angered Jamie Gonzales, and she slapped him with the back of her hands.

“Why did you put your hand on her face that day, Jeremy?” Garza asked, in front of the jury.

“Well, to defuse the situation, I didn’t want to hurt her or anything, so I was just trying to push her out of the raft,” Jeremy Pidgeon testified.

“Fair to say you tried to push her out of the raft with the least force possible?”

“Well, yeah,” Jeremy Pidgeon said.

“And the reason you pushed her out of the raft was …?”

“She was slapping at me.”

“And you felt it was necessary to defend yourself?”

“I just wanted to defuse the situation.”

He said he shouted for her to come back, but she stomped off. He hopped into the water to try to grab an oar in the river. He had just bought the paddles, he said.

“So right after this happened,” the prosecutor asked, “recovering the oars was your priority?”

“Yeah,” the defendant answered.

He testified he and a friend then looked for Jamie Gonzales for quite a while. They didn’t find her.

A jury found Jeremy Pidgeon guilty of gross misdemeanor assault, as charged. As a result of his conviction, he lost a Jiu Jitsu certification and suffered damage to his reputation, his attorney said.

On June 23, Snohomish County District Court Judge Lyon sentenced Jeremy Pidgeon to one year in jail, with all but 10 days suspended. Lyon permitted him to serve the time on work release in Enumclaw. The judge asked the defendant if he wished to make a statement.

“I don’t really have anything to say,” he said. “I want to put this all behind me and move on with my life and move forward.”

About two hours later on social media, Jeremy Pidgeon posted a picture of himself inside a vehicle, smiling.

“I’m so thankful for every good and bad thing that has happened to me in my life,” he wrote, with the hashtag, #nogooddeedgoesunpunished.

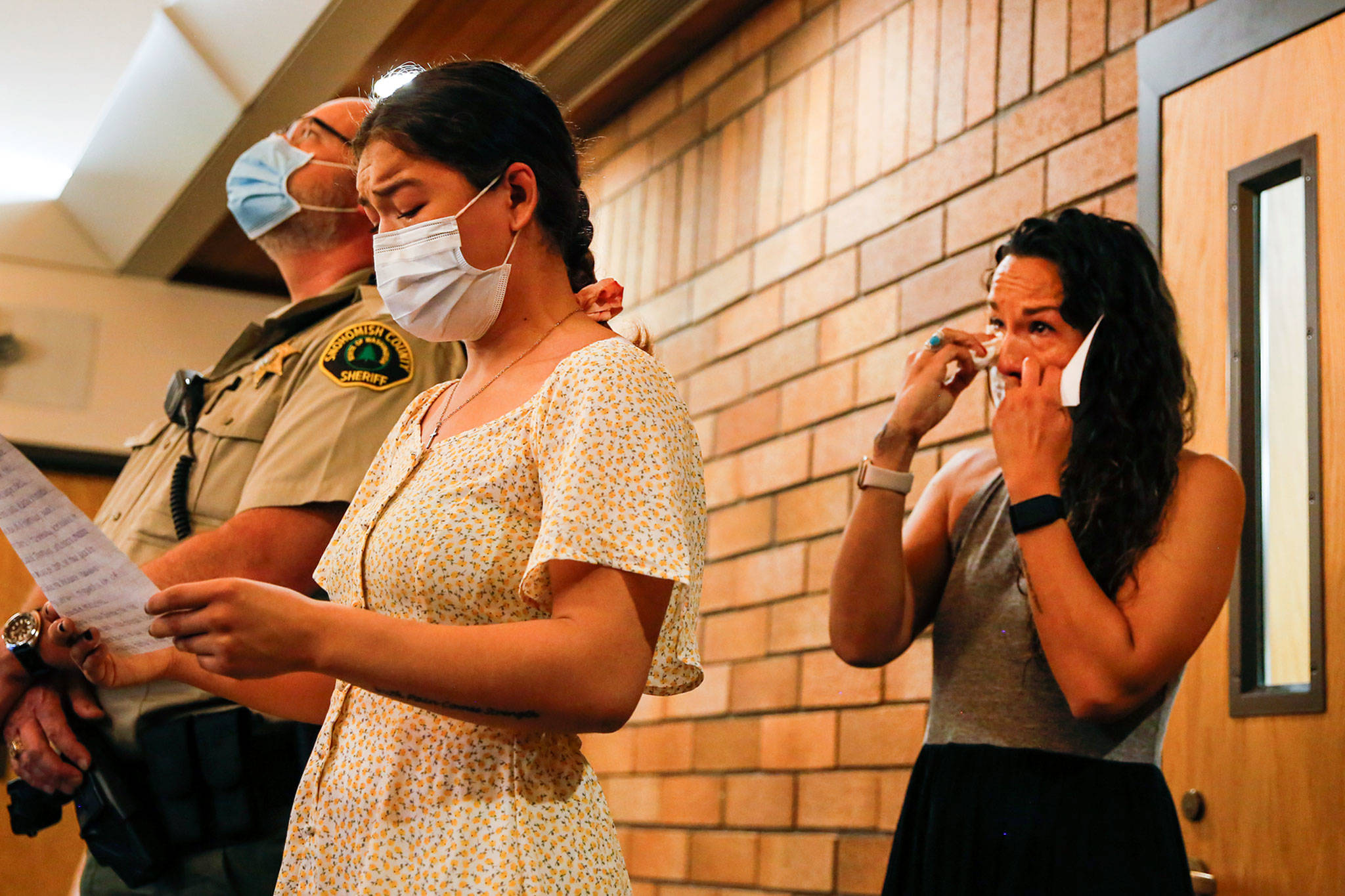

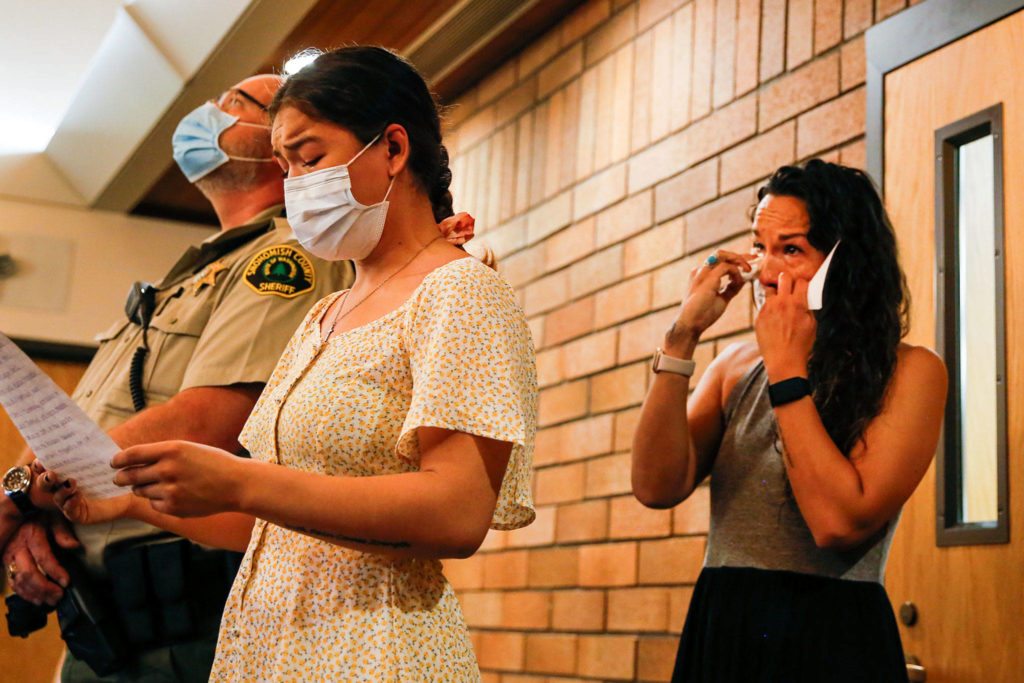

His daughters had both spoken in court, over a defense request to keep them from speaking.

“I struggle from time to time with my past and childhood with Jeremy Pidgeon,” Joessie Gonzales said. “But I finally feel safe and loved, like I was supposed to.”

Both young women said the defendant needed help.

“This incident triggered all my past fears and anxiety from my childhood, growing up being ridiculed and humiliated by Jeremy,” said Alycia Pidgeon. “It has taken the past two years to understand his destructive behavior is an issue of his own, not ours to be embarrassed by.”

‘You guys seem fine’

Society tends to put the onus of abuse on the survivor, said Kym Castañeda, a senior advocate at Domestic Violence Services of Snohomish County.

The first question people ask is, “Why didn’t the survivor leave?”

Instead, Castañeda said, we should be asking, “Why doesn’t the abuser just stop? Why do they continue to abuse?”

Castañeda uses the word “survivor” to talk about people still in abusive relationships. They’re surviving, too.

It’s hard to overstate how complicated it can be for abuse victims to come forward. One reason is that abusers are not necessarily monsters: They can do monstrous things, but the survivor fell in love with this person, Castañeda said. Survivors might believe the abuse will stop, or that the good parts of a relationship can outweigh the bad.

“There’s definitely a cycle,” she said. “The apologies: ‘I’m sorry it’ll never happen again.’ There’s also threats. The abuser might say, ‘If you tell anyone, I will do this,’ or ‘I will hurt you more,’ ‘I will have you deported,’ ‘I will out you to your family.’ There’s thousands of reasons.”

Jamie Gonzales wanted to keep her family together.

“I should have stopped things a long time ago,” she said. “But when you’re a victim of domestic violence or abuse, you feel so shameful. Like, it is the most embarrassing thing ever to let anyone think you would let someone treat you like that. You shouldn’t even treat animals that way.”

Domestic abuse crosses all boundaries, Castañeda said. It affects people from every social, economic, racial and religious background. It took a long time for Jamie Gonzales to say it affected her.

“Facebook shows life is great,” she said. “Everyone was like, ‘You guys seem fine.’ Unfortunately the girls paid for a lot of that.”

Joessie Gonzales has been coaching wrestlers at Mount Vernon High School. She’s 21, so she gets mistaken for a student. She’s still fighting, now in mixed martial arts, for her own reasons. She won a match in May.

Her sister Alycia has been working as a hostess. She stopped wrestling because her heart was no longer in it. She struggled to find motivation when she knew she wouldn’t be punished for losing, she said. Recently she made a deal with her mom to start mixed martial arts training on the condition that they go together.

One moment from the court case has stuck with Jamie Gonzales. An attorney asked her, on the witness stand, if she had a muscular stature. Jamie Gonzales smirked. She told him yes, five years ago, but that now she’s “just a mom.” She felt there was an insinuation: She does sports men do, so she must be strong enough to defend herself.

“I was trained to get in a ring, and (my daughters) were trained to get on the mats — right? — with an official that will make sure that no one is hurt at the end,” she said. “Yes, you can get technically hurt, but there’s someone there. We’re not being trained to fight our family or be abused by our family.”

Jamie Gonzales and Jeremy Pidgeon are both in new relationships.

The daughters said they have seen a big change in their mother. She used to get sick all the time. She didn’t want to try new things. You could tell, her oldest daughter said, that “her soul was so drained.” Now Jamie Gonzales wants to find ways to help other abuse survivors.

“When you live this life a certain way, and then you’re just free — I don’t know,” the mother said. “I feel like I can breathe so much better now.”

For two years, Jamie Gonzales cried each time she told her story. She can tell it without tears now.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Need help?

If you or someone you know needs a safe place to talk because of domestic abuse, you can call Domestic Violence Services of Snohomish County at 425-25-ABUSE (425-252-2873). The line is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Call takers are there to help, not to tell you what to do.

You can also reach out to the Providence Intervention Center for Assault and Abuse: 425-252-4800.

If you are worried about being heard on the phone, you can text 911.

How to listen

If you are concerned about a friend or family member who may be experiencing domestic violence:

• Talk to them. More importantly, listen to them. Call, video chat or text. Use the mode of communication they are most comfortable with, and let them know that you are there to support them.

• Don’t judge. Don’t blame or pressure. Trust them to know their situation best, and be there to support them as they navigate the difficult personal choice of whether and when to leave.

• Know the resources. Have them available for the person you are talking to, and for yourself. Anyone can call the hotlines. If you are worried about someone you care about, call and have an expert talk you through things.

• Speak up for children. If you are concerned about the safety of a child, you can contact Dawson Place at 425-789-3000, or call state oChild Protective Services at the statewide End Harm line (866-363-4276).

• Be open about your own experiences if you are in a place to do so. Talking about subjects that have been taboo, like child sexual assault, can help take away the shame and make others feel safer and less alone in reporting abuse. Investigations are more effective when people feel they can speak honestly and without fear of judgment.

• Approach every conversation with the mindset of “What do you need? How can I help?” rather than “Here is what you should do.”

Source: Snohomish Health District

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.