EVERETT — When the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office hired Calvin Walker as a probationary deputy in April 2021, his background check missed red flags, top administrators have concluded.

The deputy who conducted the check — his first one — learned Walker was among the armed vigilantes who lined First Street in Snohomish a year earlier in a self-proclaimed bid to “defend” the downtown from a rumored far-left riot, according to documents obtained by The Daily Herald this month in a public records request.

That information alone wasn’t disqualifying for a job at the Sheriff’s Office.

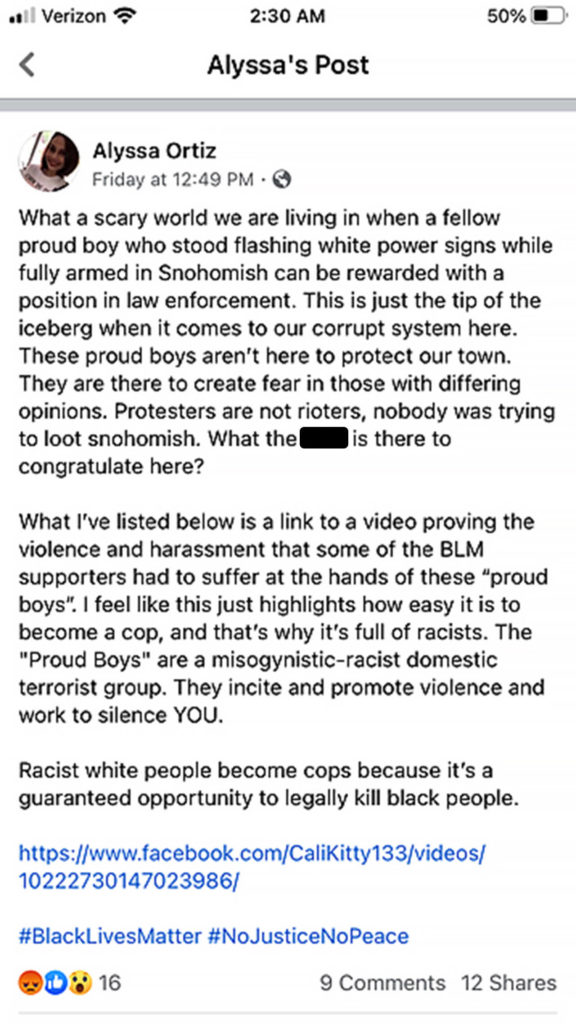

There were other signs online that suggested Walker, 23, of Marysville, had poor judgment — and allegations that he had ties to the violent hate group the Proud Boys.

He remained on the Sheriff’s Office payroll until late January, according to documents the agency provided to The Herald.

The Sheriff’s Office launched an internal investigation into Walker’s background last October, when public concern flared over a photo of Walker and Sheriff Adam Fortney, posted to the agency’s Facebook page to congratulate Walker on his graduation from the law enforcement training academy.

People identified Walker in another photograph, circulating on social media, that showed him and two other men sporting tactical gear and assault rifles on First Street on May 31, 2020. The alleged looting threats, purported to be from “antifa,” never materialized, and the situation fizzled.

Facebook users labeled Walker a racist and accused him of belonging to the violent hate group the Proud Boys, citing a patch on his vest depicting the 13-star “Betsy Ross” flag. The flag, a symbol from colonial U.S. history with many meanings, has drawn scrutiny in recent years because it has been used by white nationalist groups to glorify a time when slavery was legal.

‘Prioritize public trust’

Though other high-ranking officials at the agency recommended Walker be terminated, the sheriff initially chose not to discipline him, records show.

“Because I find that the evidence does not support any inference that you have engaged in discriminatory behavior, endorsed discriminatory behavior, or actively associated with any groups known to exhibit discriminatory behavior, I have decided not to render discipline in this matter,” Fortney told Walker in a letter Dec. 28. “Were it otherwise, you simply would not be an SCSO employee.”

The next month, Fortney changed his mind. He fired Walker.

In a second letter dated Jan. 26, the sheriff told Walker that the investigation brought to light actions that “will damage the public’s trust to an extent to which I believe you cannot recover at this agency.”

Fortney explained, in an email to The Herald on Monday, that he ultimately decided to terminate Walker because of input from the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Community Advisory Committee, which he described as a group of “active community members” from across the county that he first convened about a year ago to review such incidents.

The committee consists of 10 to 15 volunteers who are chosen by the sheriff “based on their direct commitment to and involvement with the county of Snohomish and serve a 3-year term,” according to a written program description. The group does not have oversight or authority over law enforcement matters, the description says. Instead, it serves as a “community resource for the Sheriff in the formation of strategies, development of community policing concepts, and increasing public awareness.”

When Fortney informed the board of his initial decision regarding Walker, some members disagreed.

“Following this meeting,” Fortney said in his email, “I realized that there would be members of our community who would never see the full details of this case but would believe one of our deputies is racist and would believe that I willingly chose to keep that individual as a Sheriff’s Office employee.”

Over the next few days, he wrote, he thought about the decision: “I read our Sheriff’s Office vision statement, ‘to prioritize public trust,’ and I knew that no matter what I did or how I explained it, a portion of our community would lose trust in our office.”

Controversy over Walker’s hiring raises questions about how he made his way into the sheriff’s ranks when, as one bureau chief noted during the investigation, “scrutiny that is faced by law enforcement is more intense now than ever.”

‘The mere perception’

In the wake of the events in Snohomish in spring 2020, questions swirled about whether members of white supremacist groups were among those who arrived armed. At least one of the vigilantes waved a Confederate flag. In the crowd, wearing a tactical vest with the label “Proud Boy,” was Daniel Lyons Scott, who went by the nickname Milkshake, according to a widely shared photo and live-streamed footage. (The hate group member is now facing federal charges for his role in the siege on the U.S. Capitol in January 2021.)

Snohomish residents called on the mayor and police chief to resign, accusing them of allowing a gun-carrying crowd to publicly drink alcohol, intimidate citizens and tarnish the city’s reputation.

In a June 1, 2020 radio interview, Walker told conservative KIRO-FM host Dori Monson he would have been willing to resort to other physical force or, as a last resort, shoot someone to “stand against evil” that day.

“We’re sick of police being villainized and police being targeted in these types of attacks and riots,” Walker said on the show. “We were there to protect them and help them as much as we possibly could.”

Walker added that “political correctness has destroyed the American ability” to stand up for one’s own beliefs.

The Sheriff’s Office investigation focused on the radio interview and another comment, attached to a photo posted to Walker’s Facebook account in August 2020. The image shows him in a red American flag T-shirt, shorts and cowboy boots in front of a charcoal grill. Just below the fraying hem of his denim cutoffs, a holstered handgun was strapped to his thigh.

When a friend asked whether the picture “is racist or misogynistic,” Walker responded, “it’s honestly a lot of both.”

His entire Facebook profile has since been deleted, or at least removed from public view.

Walker later told the Sheriff’s Office his remark on Facebook was a “stupid comment” responding to a sarcastic quip from his friend, who was “making light of a culture that’s offended by a lot of things.”

He repeatedly denied being racist or affiliated with anyone who has such ideologies.

Though the investigation found no explicit ties between Walker and racist groups, top sheriff’s administrators advised Walker should be terminated for violating an agency’s policy requiring employees to portray a positive public image.

“The mere perception that Dep. Walker is involved with extremist ideals by seemingly confirming a comment from a friend that he is racist and misogynistic, is truly what matters to this investigation,” Administrative Bureau Chief Norm Link wrote in a Nov. 9 memo

“Ideally, the background investigation would have caught this social media post but unfortunately it did not,” Link said. “The decision to hire Walker would likely have been different, or at the very least spawned a deeper dive into Walker’s personal conduct.”

The deputy who conducted the background check for Walker’s hiring has since attended additional training, according to the sheriff’s email to The Herald.

“Also, the Sheriff’s Office now has a procedure in place during the deputy sheriff applicant intake process where social media accounts are checked before the hiring process even begins,” Fortney wrote.

“We did not have the information we have now when we made the initial hiring decision,” the sheriff said in the email. “When SCSO employees brought additional information to our attention, we acted immediately, put (Walker) on administrative leave and began an internal investigation to determine the facts of this case.”

‘Joke or not’

Walker’s past actions offended sheriff’s personnel, some of whom are people of color, the sheriff’s investigation found. They questioned whether he was fit for a law enforcement job.

A sergeant had seen the posts circulating about Walker on social media and voiced concerns in October, giving rise to the investigation. That sergeant emailed screenshots to a supervisor on Oct. 11, including Walker’s comment labeling himself a racist.

“This is alarming to me, a joke or not,” the sergeant wrote.

His email also cited the photo from First Street and noted the controversial affiliation of the Betsy Ross flag.

“All of this is public information and can (be) found very easy,” the sergeant wrote. “All of (the) above together leads to me to have concerns about his judgement and possible Race issues.”

That day, Undersheriff Ian Huri ordered an internal investigation based on the complaint. Walker was placed on paid administrative leave.

Sheriff’s staff worried the agency’s reputation was suffering, emails show.

“As a member of this office, I am highly concerned and that this has already reflected poorly on our office,” another sergeant wrote in an Oct. 18 email to the sheriff’s investigator assigned to the probe.

The sergeant later told the investigator that, though he’d never spoken with Walker, seeing Walker’s past inflammatory marks “hits home,” and that he wouldn’t feel comfortable working with him.

“In 2021, as a person of color, it just makes me feel uncomfortable working with him, seeing the signs that I see,” the sergeant remarked during an interview. “… Everything that I’ve seen is somebody that just (has) too many red flags for me.”

Walker maintained his actions were misunderstood.

“I’ve interacted with people of different races my entire life and never had an issue with them,” Walker told the investigator in an interview Oct. 20. “I hold friends to this day, some of my closest friends are not the same race as mine.”

He chose to wear the Betsy Ross flag in Snohomish because he’s “a history buff,” he said. Only later did he learn it had been co-opted by white supremacist groups, he reported.

When rumors began circulating about such groups being present on First Street, he agreed to the radio interview to “set the record straight” that he and his companions “went down there strictly to protect the town,” he said in the internal report.

Walker was allowed to return to work on Oct. 21 to resume post-academy training.

On Nov. 9, Link concluded Walker’s “decisions and Facebook posts have compromised the integrity of our office and have already alienated and offended the employees that know about this situation.”

Walker’s “emotional response” to the situation on First Street, Link said, “is potentially a precursor to other emotional responses and/or poor decisions that Dep. Walker may make under the color of his Snohomish County authority when he becomes frustrated with circumstances that are beyond his control.”

Undersheriff Huri agreed with Link’s recommendation to terminate Walker, concurring that his actions “have tarnished the public image” of the Sheriff’s Office, records show.

Undersheriff Ian Huri informed Walker in a Nov. 16 letter that he faced “discipline ranging between a two-year letter of reprimand and termination.”

‘Heightened sensitivity’

Fortney’s first letter to Walker, dated Dec. 28, included six pages of reasoning on his decision to issue no discipline.

“I have absolutely no tolerance for employing anyone in my office that exhibits discriminatory behavior,” he wrote. “But I also am not going to throw away reason and common sense in interpreting evidence presented to me in the course of a disciplinary investigation. Such nuances likely will never make it into the headlines of the newspapers, but they are not something I can ignore when someone’s career is also on the line.”

He cited the Facebook comment as an example.

“In fact, your friend’s joke is that there is not anything racist or misogynist about it, just that someone will invariably attach that meaning to it somehow because that’s the state of the world we live in nowadays,” Fortney said in the first letter to Walker.

“Perhaps some will disagree with even the crux of this joke — that making fun of a heightened sensitivity to discrimination should also not be mocked,” Fortney wrote. “But making light of perceived hyper-sensitivity in the modern world is a very far cry from actually supporting racism or misogyny.”

Fortney said there was “absolutely no evidence” to conclude that Walker was affiliated with the Proud Boys or any such organization. He also dismissed the investigation’s focus on the Betsy Ross flag, saying the flag has been used for other purposes, including by Second Amendment rights groups “without any ties to racist ideologies or extremism.”

He noted, too, that the investigation’s findings hinge on events that occurred before Walker was hired by his office.

“Judging your pre-employment conduct as though you were an existing deputy seems to me to be an unfair standard,” he wrote in his initial letter to Walker.

Regarding Walker’s presence on First Street, Fortney said the law allows citizens to carry firearms and intervene when “someone is engaged in vandalism, mischief or stealing.”

“Here though, nothing actually happened,” he said. “There is no allegation you ever actually did anything but be present on First Street. That, in itself, is simply not enough — either for civil/criminal liability or for discipline.”

The sheriff, too, was present in downtown Snohomish on May 31, 2020. He spoke to local residents who were armed. They were Snohomish parents and business owners, “not white nationalists, they were not extremists,” Fortney later told the Snohomish County Council. An outspoken supporter of Second Amendment rights, the sheriff advised them to leave it up to the police to protect the city.

In his first letter to Walker, Fortney also told him “there was nothing inherently inappropriate or offensive” about Walker’s comments on the radio show.

“You indicated you did not want to use the firearm, but that you would not hesitate to shoot (i.e. use deadly force) if it was necessary — in other words, to defend someone from physical violence that might result in serious bodily harm or death,” Fortney wrote. “In actuality, that is an accurate, albeit generalized, recitation of the law.”

Walker’s firing came before the end of his probation period as a new hire.

“Given the facts found during the internal investigation,” Fortney noted in his statement to The Herald, “had this conduct occurred with a non-probationary employee, it would be unlikely we could terminate them.”

In his second letter informing Walker of his termination, Fortney acknowledged he had “misjudged the impacts” of his initial decision to keep Walker on his staff.

“As the Sheriff of Snohomish County, I must prioritize what is in the best interest of our organization and the community members we serve,” he wrote in the termination letter to Walker on Jan. 26. “It is our responsibility to protect and serve each and every member of our community, and we cannot do that without the public’s trust.”

Rachel Riley:

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.