Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of three stories about the history and lingering trauma of the federal Tulalip Indian School, as well as other regional boarding schools attended by Tulalip children.

TULALIP — There was no use running away, Harriette Shelton Dover recalled, when the Tulalip Indian School matron thrashed her with a horse whip from her neck to her ankles, swinging “as hard as she could.”

“Years later,” she said, “I found out that kind was also used in penitentiaries and outlawed. But it was used on us. And what were we doing? We were 9 years old and we were speaking our language.”

Matthew War Bonnet can still picture the priest’s “Jesus rope,” a thick cord with strands coming off it. He was a 6-year-old boy when authorities took him to the St. Francis Boarding School in South Dakota.

“We were hit with that and their razor straps as well,” said War Bonnet, now 76, a Snohomish resident of Sicangu Lakota descent, in testimony before a U.S. House committee in May. “One priest even used a cattle prod to hit us.”

Scenes like these were seared into young minds for over a century in the era of U.S. Indian Boarding Schools. The schools disrupted at least one generation of every Native American family, inflicting profound scars through forced assimilation, rampant abuse and death.

From 1857 to 1932, thousands of Pacific Northwest children passed through a federally mandated school at Tulalip, about 30 miles north of Seattle, where students lived under a strict military regimen. Abuse was by design, to eradicate Native culture, at hundreds of similar schools across the nation.

“Children were subjected to forced labor, neglect, malnourishment and physical and sexual abuse,” said Deborah Parker, a descendant of Tulalip boarding school survivors who now serves as chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. “Children were beaten to death. This happened routinely enough to compel operators to have cemeteries on the school grounds.”

In 2021, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation reported finding the remains of roughly 200 children in an orchard at a boarding school near Kamloops, British Columbia. Weeks later, the Cowessess First Nation announced 751 unmarked graves at the campus of another school.

The discoveries forced non-Native people to acknowledge atrocities that Indigenous families have grappled with for years, often silently. Last year, the U.S. government launched an investigation into its own past practices. An initial report from the U.S. Department of the Interior in May confirmed at least 500 Indigenous children died in about 19 schools. Hundreds of other institutions across the country had cemeteries on school grounds. The report says further investigation will likely reveal the number of Native American students who died “to be in the thousands or tens of thousands.”

At Tulalip, at least 31 graves are nameless on the south edge of the Mission Beach cemetery. Local historians say the boarding school campus stood near this lawn in the late 1800s. Names have worn off some headstones. Moss grows on others. Along a back fence, more than a dozen makeshift wooden crosses stand in a row. Here, in the oldest part of the cemetery, are “lots and lots” of unknown graves, said Candy Hill-Wells, funeral services officer for the Tulalip Tribes. Marked headstones nearby date back to the late 1880s, and at least six school-age children were buried feet away in the early 1900s.

Tribal leaders don’t know if children or adults are buried in the unmarked plots, but now that people are paying attention, there’s momentum to find out. Oral history has it that school leaders “just buried the kids right outside the school,” Tulalip historian Les Parks said.

If so, the graves are among the few artifacts of the local boarding school, an institution that is key to understanding the history of the Tulalip Tribes.

Under the Treaty of Point Elliot in 1855, the government ordered the Samish, Skagit, Suiattle, Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Stillaguamish and other allied tribes to live on a marshy sliver of Snohomish ancestral land along Tulalip Bay.

For almost a century, a boarding school served as the reservation’s centerpiece.

At Tulalip, the erasure of Native culture began under the banner of a Catholic mission school in 1857. Later, the federal government inherited the campus. Thousands of Indigenous boys and girls, abducted from across Western Washington, passed through the federal school. Like many ugly parts of history, much of the story has been hidden, forgotten or preserved only from the vantage point of people who did the damage.

Yet even the official records show disease and death came in waves.

In 1904, for example, the Tulalip school had 140 students. Over the next five years, The Daily Herald confirmed, at least nine students died. On each annual roster, a handful of names dropped off the next year, inexplicably.

‘At a cellular level’

When elders share stories from their school days, they endure the pain again. Their brows furrow. Their breaths deepen.

Arnold McKay, of Lummi descent, attended the Tulalip school from 1919 to 1927.

“I look back on the health of the students now, and I say the government failed miserably in that work,” he said at a Marysville School District forum months before he died in 1994. “They really, really honest to God neglected us.”

Across the United States, the government sent kids as young as 4 to one of at least 408 federally supported Native American boarding schools, where school officials punished students through solitary confinement, withholding food, slapping and flogging, according to the Interior report released in May. At times, older children were forced to punish younger children.

“We heard stories of such immense abuse that some of our elders can’t hear from one of the sides of their head because they were hit,” said Parker, who has collected stories of survivors and their descendants as part of the Interior research. “We know that one of our young girls was sent to the basement (at Tulalip) and she was chained to a heater and beaten daily.”

Boarding school survivors often withheld those painful memories from their own families, said Teri Gobin, chairwoman of the Tulalip Tribes.

“It left such scars on their life,” Gobin said.

School officials whipped students if they “did anything out of line,” Gobin said. “They had to adapt so they wouldn’t get beaten.”

“The hurt, the physical hurt, was not as bad as how I felt in my own mind,” Shelton Dover explained, in a recorded interview more than 65 years after the buggy whip “strapping.”

The pain is still fresh for War Bonnet, who spoke this month with a Herald reporter.

“They put a lot of rage in us, and … a lot of us became abusers of ourselves,” he said. “We became abusers of our families. We became abusers of our communities. And our grandchildren are suffering because of that.”

That was learned behavior. The priests at the St. Francis Boarding School in South Dakota would often make the children abuse the other children, War Bonnet said. To cope with the trauma, War Bonnet distracted himself.

“I didn’t stop to think about it,” War Bonnet said. “I just worked, worked, worked all the time, for 14, 16 hours a day. I would work, I would work. … But when you stop working, like I did 10 years ago, you’re still thinking about these things.”

As early as the presidency of George Washington, official federal policy advised assimilation as the cheapest way of “subduing” Native Americans, so white settlers could take their land and detach them from Indigenous ways of life, according to the U.S. Interior report. Schools were weapons to accomplish those goals. In some families, up to three generations spent their childhoods under the watch of matrons, priests and teachers, instead of their own parents.

“A vast majority of us have our own family members who went to boarding school,” said Matt Remle, Native American liaison for the Marysville School District.

Many survivors don’t talk about their experiences much. Remle, who is Hunkpapa Lakota, said his grandmother only shared fragments about her years in a Catholic boarding school, often cursing.

“Goddamn those nuns,” she would say.

Tulalip elder John Campbell, 75, said his mother never spoke about her time in the Tulalip Indian School.

“It’s heartbreaking all the stuff that I didn’t know that went on,” he said. “The government was essentially kidnapping kids.”

In 1883, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs banned any religious or cultural “evil practices” under the Code of Indian Offenses. For Coast Salish tribes, it meant families could not sing songs or tell oral stories, except in secret. Fewer than 20 Lushootseed speakers survived the decades when speaking a Native language was deemed a crime.

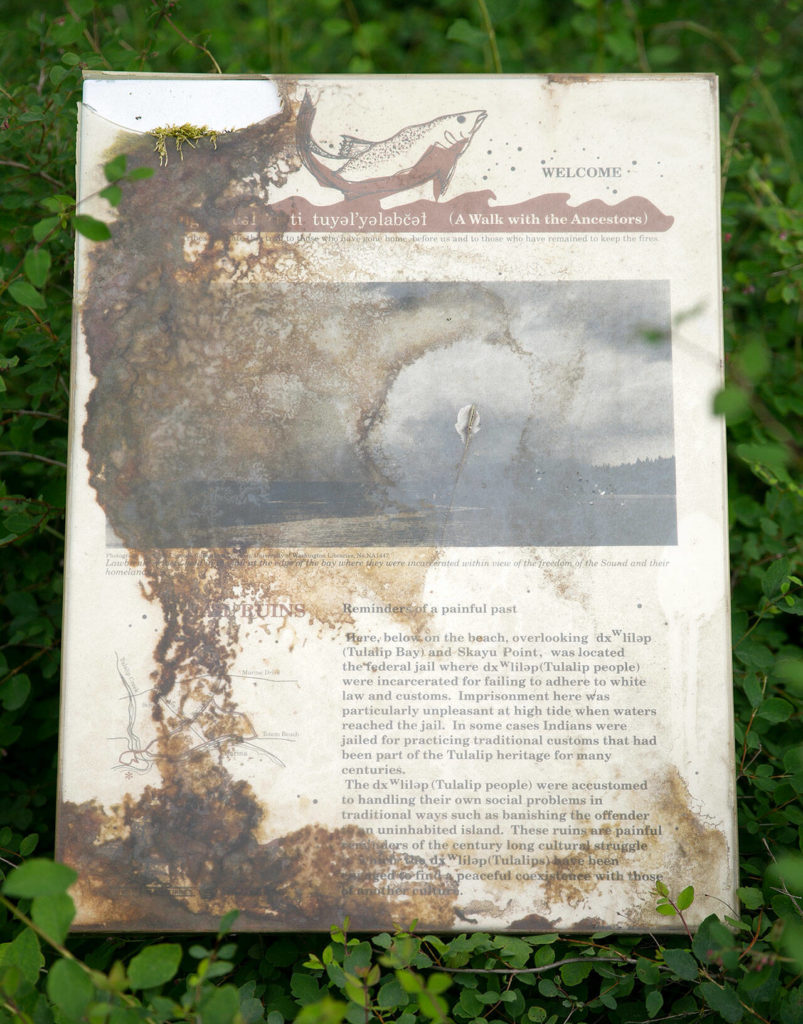

As a child, Celum Young spent three nights in a tiny concrete jail cell on the shore of Tulalip Bay. Her crime was saying one word of Lushootseed, according to her family. She did not know if she would survive the time behind bars.

“What really was sad about the jail cell is when the tide comes in, the water would fill that jail cell up,” said her great-granddaughter Chelsea Craig, assistant principal at Quil Ceda Tulalip Elementary.

Young’s indoctrination at the Tulalip Indian School began at age 5. Until her teenage years, the school only allowed her to go home for two months per year.

Native ways were “beat out of my grandmother in the name of education,” Craig said, and that pain has been passed down “from generation to generation, at a cellular level.”

Often, Craig has heard people say things like, “Oh, why don’t you Indians get over it? That was a long time ago.”

“No, it wasn’t a long time ago,” she said. “And it’s genocide our people survived.”

‘We’ll kill you’

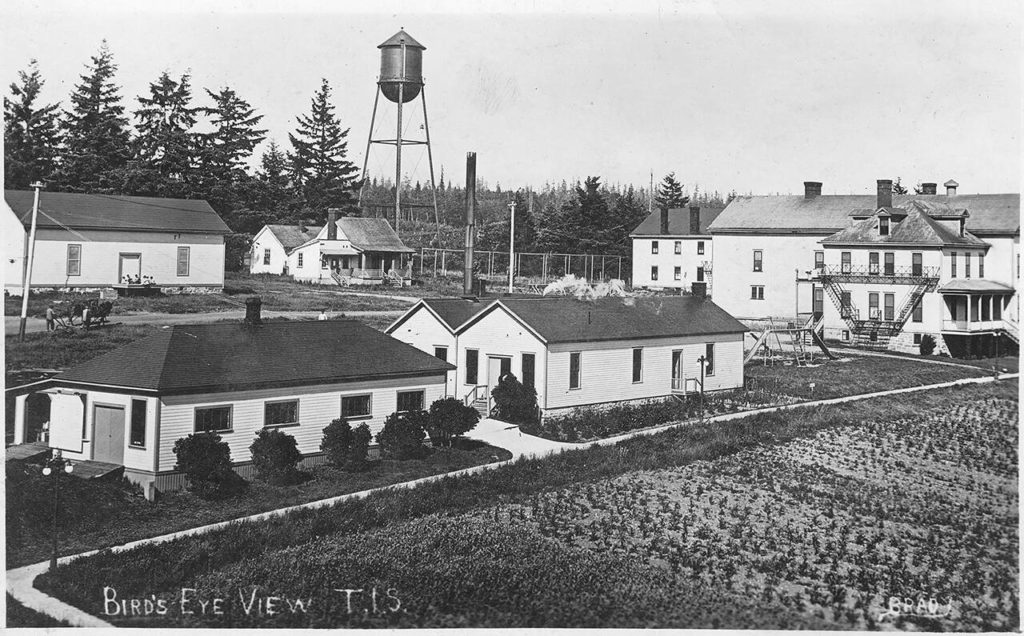

The Tulalip Indian School offered a first- through eighth-grade education, with room for 200 pupils. The federal school stood a stone’s throw from the bay. Buildings were plain, stark, impersonal: a boy’s dorm, a girl’s dorm, a church, the dining hall, a mill, the main school. Most were painted white with dark accents and gabled roofs, typical of northern European architecture.

Only two buildings survive. The dining hall, with an expansive wooden deck overlooking Tulalip Bay, has been “refurbished back to its original way,” Gobin said, giving a tour to a reporter. The tribes still use the hall and the old Indian Agent’s office, in a sense reclaiming and repurposing a part of the past that is too important to forget.

“If you go downstairs in the basement, the very back, the kids that got sent there for being bad, got locked up down there — they carved their names into the wood,” said Misty Napeahi, vice chair of the Tulalip Tribes.

Fleeing a boarding school was a crime. According to survivors’ accounts, authorities who caught escaping students hogtied them by the ankles and wrists, then left them in the halls for other students to see, Gobin said.

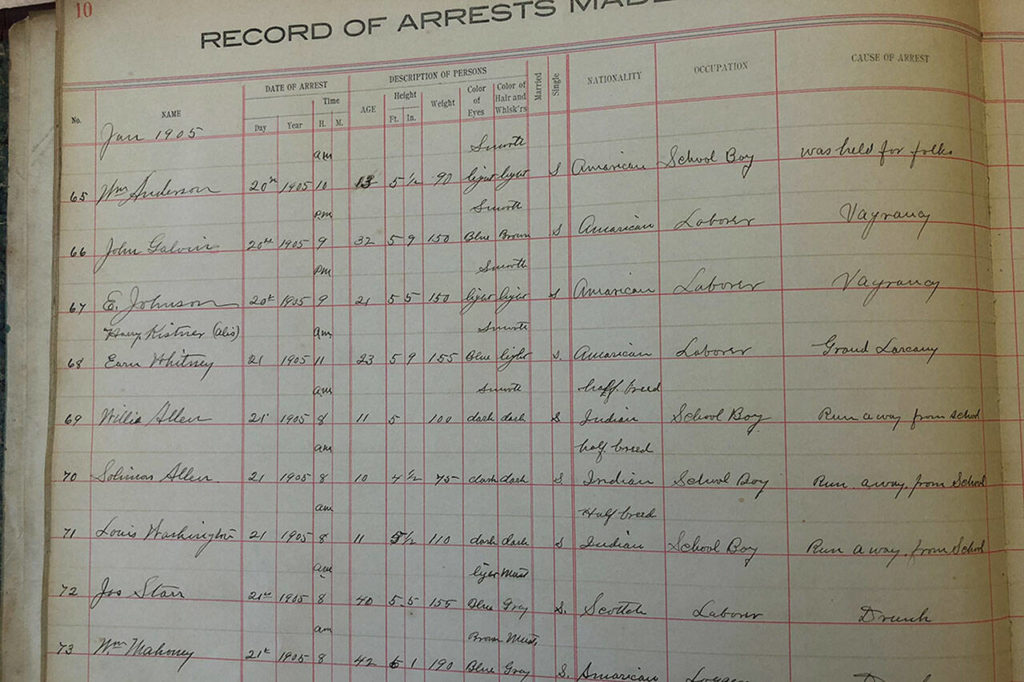

A police record of arrests on the Lummi Reservation in January 1905 names three “half-breed Indian” students accused of running away from school: Willis Allen, 11; Solimon Allen, 10; and Louis Washington, 11.

On June 14, 1907, the Seattle Daily Times published a brief story about Eugene Sheldon, a teenage student at the Tulalip school, who wrote to a federal judge that the superintendent “kept him locked up and in chains at the reservation and refuses to file any charge against him in spite of the fact that he has not been sentenced to imprisonment and is not under indictment.”

Sheldon claimed he’d been locked in a wooden shed “which is both uncomfortable and dreary and that the state of affairs from which he asks relief has been going on ‘for a long time.’”

When two Lummi boys tried to run away from the Tulalip school, officials whipped them so hard it took them 45 minutes to crawl from the school back to the dorm, according to stories of abuse recounted at a forum in 2017.

“Now, the mindset is the white man dictates the world the Indian lives in,” said Terry Fast Horse, 52, a Tulalip resident of Lummi and Lakota descent. “If an Indian don’t like it? We’ll kill you. If you don’t conform, we’ll kill you, we’ll beat you. You’re praying? We’ll beat you. You talk tongues? We’ll beat you. You want to breed your own? We’ll kill you.”

If Native families didn’t enroll children in boarding schools, the government could withhold food and supplies. Tulalip parents could be hauled to the jail on the shore of the bay. In the early 1900s, Tulalip tribal member William Robert Sheldon spent six months in the tiny concrete federal lockup for withholding his daughter Bernice Williams from the school. According to Williams, he had feared for her health: His stepson nearly died of pneumonia as a student.

Throughout the federal school’s existence, the hospital in Tulalip only had one physician at a time. In his tenure from 1894 to 1920, Dr. Charles Milton Buchanan’s attention was stretched thin: He served as Indian Agent for the reservations at Lummi, Suquamish, Swinomish and Tulalip. Starting in 1901, he was also superintendent of the Tulalip Indian School.

Diseases spread among the dozens of students packed in the dorms at Tulalip. Williams said her family members died at the school around the age of 16.

“At that time, they weren’t diagnosed too clearly,” she said in an interview with historians recorded in the 1990s. “But the oldest one, I believe it was tuberculosis.”

Many succumbed to what was reported to be tuberculosis, pneumonia or the flu.

“Tuberculosis — did every one of your brothers and sisters die from that?” an interviewer asked Craig’s great-grandmother in a VHS recording from 1982.

“They all died (from) tuberculosis,” Celum Young answered, listing off seven siblings. “Even my father died from it.”

Shelton Dover witnessed insurmountable suffering as a student, like her sister’s battle with tuberculosis.

“It’s a lingering death, it goes on hour after hour until the person is so exhausted they just look like they’re sleeping but they’re really in a coma,” said Shelton Dover, also known as Hiahl-tsa, in an interview with a student conducting research in the 1970s. “Her pain went on for hours and days and weeks. When I think of that, I’m not thankful to the white man for anything. It took me 20 years to get over the awful hurt of her death.”

She lost many of her school peers, too.

“All of them were teenagers,” Shelton Dover wrote in her autobiography. “In just two months, five young people died: my sister, Marguerite Jules, Cecilia Weeks and her cousin Edwin Weeks and Edwin Hillaire.”

Cold temperatures in the dorms, hunger and the long days of school and work killed her classmates, she said. There was never a doctor available and never any medication.

“I was always told to sit still and I always did,” Shelton Dover wrote. “I could sit, it seemed like, by the hour; just sit absolutely still and watch my playmates die.”

‘For so long’

Official records from 1905 to 1907 show enrollment shrunk each year at the Tulalip Indian School, from 147 students to 124.

Those rosters fail to note students who died. Some missing names can be found on headstones at Priest Point and Mission Beach. There are at least 14 student graves between the two cemeteries.

Three of the buried students did not survive past the 1904 roster.

Annie George, 10.

August Sam, 14.

Alfred Shelton, 12.

At least one more died in 1905.

Walter Shelton, 5.

And one more from 1906.

Cecelia Jules, 10.

She’s buried near four more students from 1908.

Benjamin Johnson, 8.

Sarah Jones, 14.

Francis Shelton, 10.

Minnie Young, 6.

As for the many others who died in childhood, few records from the school at Tulalip predate the federal school era. Many people who live and work on the reservation know little about the mission school’s dark past.

The Interior report confirmed burial sites at 53 Native boarding schools across country. Some were unmarked, though locations and the exact number of graves were not disclosed out of concern for grave-robbing. So the report doesn’t specify if any were counted at Tulalip.

School census records show Indigenous children who died at Tulalip were buried there, often far from home. Likewise, some children plucked from Tulalip families died hundreds of miles away at other schools.

Shelton Dover, McKay and other boarding school survivors saw many of their friends taken across county and state lines for “treatment” at sanatoriums.

Government agents drove Stan Jones Sr., or Scho-Hallem, to the Cushman Indian Hospital in Tacoma at age 9. It had been a boarding school until 1920, and Jones was forced to live there from 1935 to 1938. He came to believe the hospital was another way to carry on the mission of boarding schools — severing Native kids from their families, forcing them to speak English and supplanting their culture.

“This is supposed to be a hospital, but they had them doing boxing matches (and) they had school,” said his daughter, Gobin, 64, the tribal chairwoman. “It was just another way to do a boarding school, because they got money for every Native student that they had.”

Jones also believed staff filled quotas for cash. He saw other Tulalip children placed in hospitals for tuberculosis, despite being healthy, like himself.

“We heard they were actually using the kids to experiment with new medicines on them,” Jones wrote in his autobiography. “Two men my age that were in Cushman found out when they were adults that they had a lung removed.”

Like at the Tulalip school, if kids did something wrong, they were abused.

“One day I did not clean my area and I was punished by being put in a closet for a period of time,” Jones wrote. “As I was in there I overheard the nurses talking. One of them said that she had been visiting the other patients in Ward D and had been praying for a young man named Jack Jones and he had just died. I started crying and they asked why I was crying; I wouldn’t say anything and they didn’t know he was my brother.”

Norman “Jack” Jones died at age 14.

Years after the Tulalip school closed, the Tacoma hospital stayed open.

“I had been there for so long, I had forgotten about home and I thought my family forgot about me,” Jones wrote.

Separation drove a wedge into countless families. The 106-page report from the Interior department found boarding schools deliberately disrupted the “Indian family unit.”

For decades, the government forced Tulalip students of high school age to live 275 miles away at Chemawa Indian School, north of Salem, Oregon. It’s one of four off-reservation boarding schools still operated by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education.

Tribal governments did not gain the right to run their own schools until 1975, and parents could not deny their children’s placement in off-reservation schools until the Indian Child Welfare Act passed in 1978.

Parker, the leader of the healing coalition, testified in the nation’s capital the day of the Interior report’s release.

“This is a historic moment,” she said, “as it reaffirms the stories we all grew up with.”

Parker is seeking justice for people like her relatives, who were deeply scarred by the federal schools, as well as for those who did not survive. Interior researchers compiled over 98 million pages of records from the American Indian Records Repository to begin to uncover what happened.

It has been a massive undertaking to peel back a whitewashed history.

“When you say ‘boarding school,’ I don’t think anybody quite realized what it was that was happening to the Indian children,” Shelton Dover said in the 1970s. “… My professor of history referred to Indian reservations as ‘concentration camps’ or ‘penitentiaries,’ and it surprised me that I was saying, ‘How right you are.’”

Shelton Dover was one of the few survivors who talked publicly about her time in the boarding schools. She dedicated much of her life to preserving endangered tribal traditions and artifacts of Coast Salish history. She died in 1991, at the age of 86.

A few years later, a construction crew excavated land for a new dental clinic off 76th Place NW, along Tulalip Bay.

“We started finding this ash,” Glen Gobin said. “So I took the time to dig through it, trying to find the bottom, and I hit something hard at the bottom. What we found was the furnace for the girls’ dormitory.”

His grandmother, Celum Young, had never told him much about her time in the dorms. But it was like he could feel her close by.

“I just felt the connection and the feelings come over you. My grandma would’ve been here, she would’ve been down here at some point,” he said. “Even though it was all buried — we’d moved on, it seemed like you dig this up and it brings it back to a reality.”

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Read the rest of this series, Tulalip’s Stolen Children.

Part 2: Unearthing the ‘horrors’ of the Tulalip Indian School

The Tulalip boarding school evolved from a Catholic mission into a weapon for the government to eradicate Native culture. Interviews with survivors and primary documents give accounts of violent cultural suppression under the guise of education at the “Carlisle of the West,” modeled after the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Part 3: ‘Keep your Indian alive’: After decades of outlawed culture, a Tulalip revival

Boarding schools scarred Indigenous children for life. In turn, their children and grandchildren have suffered. How have those harmed by the Tulalip Indian School — a cornerstone of the reservation since its inception — begun to heal?

Resources for boarding school survivors and their families

If you need to talk to someone now:

CARE Crisis Line: 425-258-4357 or 1-800-584-3578 (N. Puget Sound); Online Crisis Chat (24/7/365).

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

Crisis Prevention & Intervention Team: 425-349-7447 (Snohomish County)

WA Warmline: 877-500-9276 or 866-427-4747.

Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Helpline: 1-800-662- HELP (4357)

National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-HOPE (4673)

Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-SAFE (7233)

Find long-term support:

The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Directory.

The Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies Directory.

The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Directory.

Get connected:

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.