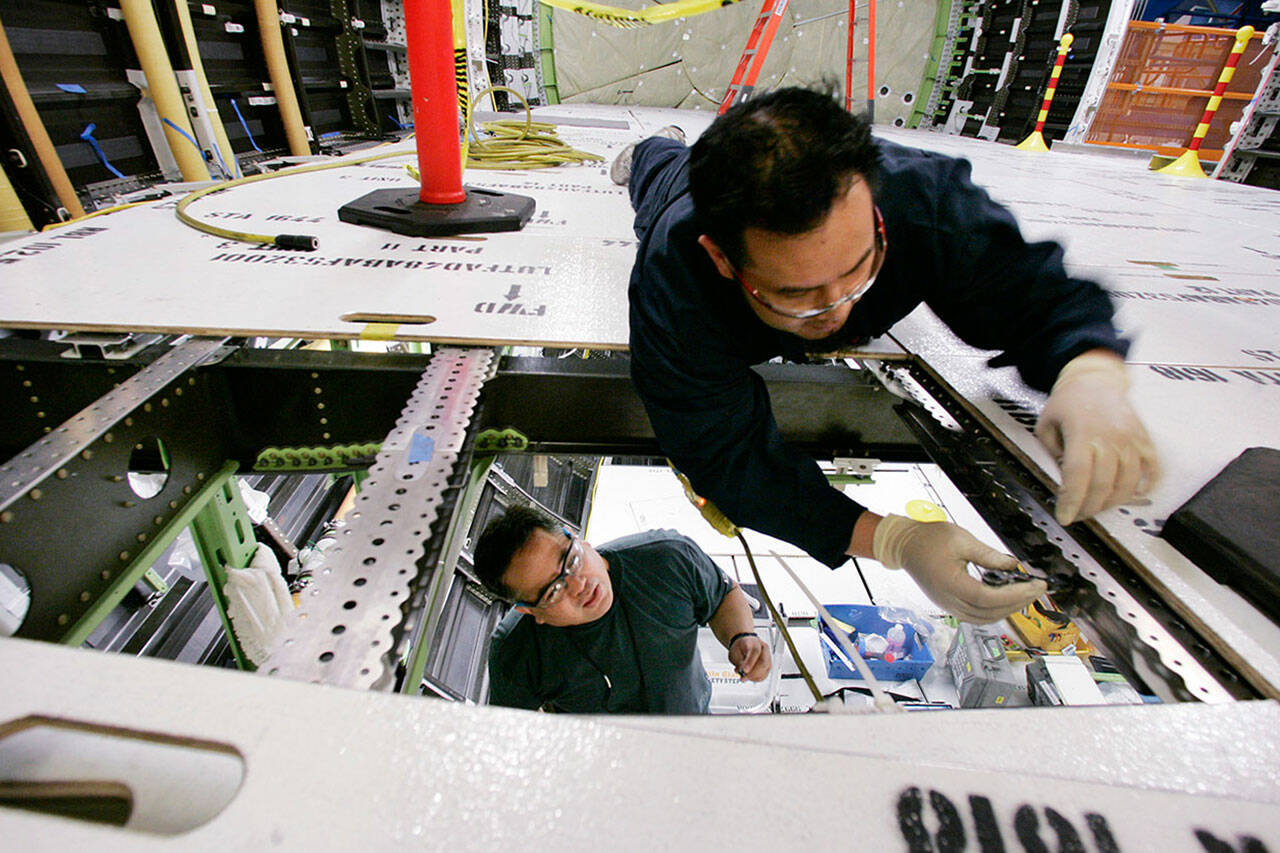

Editor’s note: This is part of ongoing coverage examining the dangers of chemical exposure to Boeing workers in the Puget Sound region. According to records obtained exclusively by The Daily Herald, some workers at the aerospace company’s Everett plant are still exposed to carcinogenic chromium at levels above regulatory limits.

EVERETT — An industrial hygienist for the Boeing Everett plant warned in 2020 that “literally hundreds of Boeing employees are at risk” of developing lung cancer or other forms of cancer — “regardless of respiratory protection” — because of an industrial poison that has been a key ingredient in the airplane production for decades.

Airborne levels of hexavalent chromium “greatly exceed the legal permissible exposure limit” in the factory’s paint operations, said company compliance manager Jennifer Allen in an email to colleagues arguing for the elimination of the chemical in the manufacturing process.

“As for employee health and safety, there is no chemical exposure more severe or of greater concern than chromate primer application in Boeing facilities Enterprise-wide,” said Allen, an industrial hygienist, or specialist in analyzing workplace hazards.

Hexavalent chromium, a long-established carcinogen often abbreviated as Cr(VI), is still used by the company for its anti-corrosion properties, despite its No. 1 rank on the company’s list of chemical concerns, records show.

Allen’s message is among hundreds of pages of internal corporate documents, discussed in depositions of company officials last year, that underscore the risks chromium and other controversial chemicals still pose to Boeing’s manufacturing workforce.

In the early 2000s, emails show, the company lobbied to keep the regulatory limit “AS HIGH AS POSSIBLE” when the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration was updating its “permissible exposure limit” for hexavalent chromium.

But even after negotiating a higher limit for painting large aircraft parts — and getting a deadline extension from the state to comply with the rule — airborne chromium levels “in some areas” of the Everett facility still exceed the standard that took effect more than 10 years ago, the plant’s lead industrial hygienist testified in a deposition last January.

‘The bare minimum’

The depositions were taken in a series of lawsuits, brought by families of former factory workers who claim that chemicals used on Boeing’s factory floors caused “catastrophic” birth defects in the children they had during their time working for the company. The cases span 40 years, involving two fathers who were mechanics at the Everett plant and one mother who worked at a factory on Boeing Field that has since been demolished.

Last fall, the company reached a settlement with one of the children, Marie Riley, now a 42-year-old North Bend resident, still living with a defective heart. Attorneys notified King County Superior Court of the out-of-court settlement in a Nov. 7 joint motion. The amount was not disclosed. The other two lawsuits, filed in 2018, were still pending as of this month.

Boeing, represented by Seattle-based law firm Perkins Coie, has denied that the plaintiffs’ birth defects were caused by chemical exposure, according to court filings. Company health and safety professionals have testified that Boeing has always taken adequate steps to protect its employees — especially those who handle hexavalent chromium — with respirators, ventilation and health monitoring.

“Boeing’s philosophy was always not to do the bare minimum, but to — to reduce levels as low as possible through the right controls and respiratory protection for inhaled components and contact with chemicals,” testified Boeing Environment, Health and Safety Director Ken Drew in a February 2022 deposition.

“Employee safety is paramount to being able to build the aircraft,” Drew said. “So the last thing the company wants to be known for is killing employees, you know, 20 or 30 employees for every airplane. That would be ridiculous. We’d go out of business.”

The Herald obtained transcripts from eight depositions of former and current Boeing employees, including more than a hundred exhibits of internal memos, scientific literature and other company documents. The company has declined to comment on any of the contents. Boeing spokesperson Jessica Kowal has said the company does not comment on litigation as a matter of policy.

‘As high as possible’

Over the years, the company has phased out some toxic chemicals and cut back on the use of others. Boeing has also been exploring alternatives to chromium primers for more than a decade, records show.

In the meantime, stronger safety rules, improved worker education programs and better ventilation have reduced the risk of adverse health impacts, according to the depositions.

However, many of the chemicals at issue in the lawsuits are still common in the factories. For example, methyl propyl ketone (MPK) and corrosion-inhibiting aerosol sprays have also been the subject of years of controversy and complaints from employees.

“Boeing is choosing to use highly toxic chemicals every day in its operations,” plaintiffs’ attorney Michael Connett, a partner at Waters Kraus & Paul, said in an August interview. “OK, that’s fine. But you now have a heightened duty to make sure that your workers are protected from those chemicals. And unfortunately, what we have found is that too often at Boeing, it’s production that they prioritize, not safety of their workers.”

Many of OSHA’s regulatory limits for various chemicals have long been recognized as too high.

The agency itself recognizes “many of its permissible exposure limits (PELs) are outdated and inadequate for ensuring protection of worker health,” according to its website, which lists alternate occupational exposure limits endorsed by other agencies.

But only OSHA’s limits are legally enforceable in Washington workplaces — and only through air monitoring can violations be discovered. Industries are required to keep employee exposure levels at or below the thresholds, to the extent “feasible,” using a combination of safer work practices and “engineering” safeguards, such as ventilation improvements.

“Boeing cannot prove that elimination of chromate primers is infeasible,” Allen wrote in her June 2020 email, “which is a regulatory requirement if we continue to use hex chrome primer.”

She added that Boeing’s health and safety branches “expend significant resources both in monitoring exposures and the health status of exposed employees, via medical surveillance examinations.”

In 2004, when OSHA was considering a new limit for hexavalent chromium concentrations in workplace air, Boeing “provided intensive input to legislative and regulatory negotiations during (the) rule making process,” according to internal company documents.

“WE ARE PRIMARILY INTERESTED IN PERSUADING OSHA TO KEEP THE PEL AS HIGH AS POSSIBLE,” a Boeing regulatory analyst wrote in a 2004 email seeking input from company scientists on the change. “This would include technical infeasibility matters, as well as medical studies to justify our position about the hazard levels.”

‘Ongoing research’

Two years later, OSHA announced a dramatic reduction in its occupational limit for hexavalent chromium, from 52 to 5 micrograms per cubic meter. The limit is calculated as an eight-hour time-weighted average, meaning that over the course of any eight-hour shift, the average exposure cannot exceed the limit.

But Boeing negotiated an exception to that rule — a special provision for aerospace painting. Regulators and the company “settled on” 25 micrograms per cubic meter, says a 2009 internal presentation by the company’s Hex Chromium Reduction Team, an exhibit in one deposition last year.

The presentation mapped out an “overarching strategy for compliance,” including ventilation upgrades and other improvements “through design changes, substitution, technology investment and process refinement.”

The other part of the strategy was to “engage proactively” with regulators and argue that some protection measures aren’t possible.

An italicized line at the bottom of the slide notes: “Employees are protected from exposure through use of PPE,” or personal protective equipment.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, part of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published a report in 2013 recommending that “airborne exposure to all (hexavalent chromium) compounds be limited to a concentration of 0.2 (micrograms per cubic meter)” for an eight-hour time-weighted average exposure in a 40-hour work week.

In other words, the OSHA regulatory limit on hexavalent chromium applicable to Boeing’s paint operations is 125 times the maximum endorsed by the CDC to “reduce workers’ risk of lung cancer … over a 45-year working lifetime.”

Though the new OSHA regulations took effect in 2010, Boeing obtained a “variance” from the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries that extended its deadline for compliance at the Everett site, according to department records.

In a 2010 letter approving the variance, the department cited Boeing’s “ongoing research to identify a suitable chromate-free substitute priming material.”

“This research resulted in identifying non-chromate primer for corrosion protection and use with composite materials like those used in the 787,” the department said in the letter. “For other airplane lines ‘Phase 1 Round 3’ tests are under way with a variety of Boeing suppliers. However, chromate-free priming materials compatible with aluminum skinned aircraft is still likely years away from implementation on the production lines.”

The state agency also recognized the company’s “multi-disciplinary approach to reduce hexavalent chromium exposures.”

“A number of internal and external organizations have been working on this effort for several years beginning in 2007,” the letter states. “Contributors have included the painters, industrial hygienists, site ventilation experts along with consulting engineers, aircraft engineers, design and manufacturing engineers, Boeing Research and Technology, and Operations leadership.”

Public records show the variance was revoked by the state agency in 2016, when the company indicated it was “no longer needed.”

‘Many overexposures’

Air monitoring reports in the following years still documented airborne chromium concentrations above the updated OSHA limit in parts of the Everett factory.

Among the deposition records, an annual air monitoring report from 2016 noted that hexavalent chromium levels still “frequently” exceeded a concentration of 25 micrograms per cubic meter in jobs involving the painting of large aircraft.

In fact, in some areas surveyed, historic data suggested the problem was getting worse.

For a sample from one section of the 747 program, the “mean chromium exposure level” had increased to 11 times the OSHA limit, compared to roughly twice the limit four years prior.

“As always, many overexposures with some improvements throughout the factory,” Michele Czajka, an industrial hygienist for the 777 program, wrote in an email when forwarding the report to a colleague.

In a deposition last January, Czajka explained that the surveys measure air samples collected from outside of a worker’s protective gear, so the data is not representative of what a worker is actually breathing if the equipment is worn properly.

“It’s not truly an overexposure because they are protected by the respirators they are wearing,” she said.

In addition to respirators, painters are also required to wear coveralls and gloves.

Based on statistical analysis, the 2016 survey concluded that ventilation and respiratory protection were enough to protect workers from the excess levels of chromium in the surrounding air.

Annual medical exams and questionnaires were also required for “those employees with spray painting work assignments 30 days or more per year,” the survey says.

During Czajka’s deposition, a plaintiff’s attorney raised questions about unprotected employees who might walk by painting operations while en route to other factory areas.

“There’s always something that you can do to protect yourself more,” Czajka said. “I can avoid driving. If I avoid driving, I avoid all of the risks that driving entails. But I still need to drive. So I still do it.”

‘Oppressive work environment’

In 2015, a Boeing final assembly manager acknowledged “widespread concerns raised about long-term work with MPK,” a “highly volatile & flammable solvent” that rapidly vaporizes, company emails show.

“When it vaporizes, MPK creates an oppressive work environment in which our mechanics report headaches, nose bleeds, etc.,” the manager wrote in an email to company health and safety experts.

At the time, the company was exploring an alternative. But MPK is still widely used at Boeing Everett to clean floors, testified Rene Irish, the site’s lead industrial hygienist, in a deposition last January.

“It comes with hazard warnings,” Irish said, “which is why everybody has to wear gloves when they’re using it and the proper PPE.”

The deposition records also raise questions about whether safety rules are consistently enforced in the fast-paced factory environment.

A 2019 internal audit found safety lapses in the 747 and 767 programs at the Everett Modification Center, including “noncompliance for PPE use” across the programs and work areas.

Three of four workers interviewed were not using the correct type of respirators even when spraying chromium primers. Four of 12 chemical users working in confined spaces did not have respirators.

Surfaces in one building had “significant accumulation” of chromium primer. Door handles of paint booths were “coated with yellow overspray” from the chemical.

Respirator users were also surveyed as a part of a 2019 annual assessment. The survey results included a list of anonymous written comments.

“If I am using MPK and the half mask and my eyes are stinging/burning from fumes, are my eyes absorbing the fumes?” one person asked.

Another remarked that “if the person cares enough to protect themselves, the availability (of respirators) is there and easy.”

One comment sticks out, in all capital letters:

“I DO NOT AGREE THAT THE SPEED AT WHICH WE ARE REQUIRED TO WORK FOR PRODUCTION RATE MAKES THE USE OF PPE EASY.”

‘Breathing issues’

In January 2020, the state Department of Labor and Industries assessed $4,800 in fines against the company after several security guards at Boeing’s Everett site complained of “headaches, irritated eyes, sporadic chest pains and other breathing issues” as a result of chemical exposure.

The citation stemmed from an incident the previous month, when two Boeing employees sprayed a brand of corrosion-inhibiting compound, Cor-Ban 35 aerosol, in building 45-335 without warning security officers at a nearby guard station, department records show.

The guards, Allied Universal employees, were not wearing protective gear at the time, and the required ventilation system wasn’t used, an inspection found.

Last year, a former Allied Universal security guard sued Boeing, alleging that she was repeatedly exposed to the spray while working in building 45-335 in 2019 and suffered lasting health problems as a result.

Cor-Ban 35 and other variations of corrosion-inhibiting compound, or CIC, are among the chemicals blamed in the birth defect litigation, too.

Irish acknowledged during her deposition that “usually the employees don’t like the strong smell of the CIC, and it can cause headaches and, yes, respiratory irritation.”

When used incorrectly, Irish explained, the aerosols can generate a lot of “overspray,” or particles that linger in the air rather than sticking to the targeted surface.

In 2019, there were concerns among Boeing employees about CIC spray leaking into areas of the 777 program where unprotected employees work, the deposition records show. The issue was summarized in an email, shared with Irish and a safety and health director.

“According to several employees and managers, the fumes cause eye, nose, throat, and skin irritation,” says the email. “In addition, customarily, employees who work on the aircraft often bring fans to cool the temperature around them. The fans suck all of the fumes into the aircraft making working conditions unbearable for some employees.”

“Allegedly, this issue has been addressed with senior management and at the executive level,” the email says. “however, nothing has been done.”

Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly attributed a statement about employee safety concerns, made via email, to a Boeing safety and health director. A Boeing spokesperson has clarified that the message was forwarded to the director. The identity of the e-mail’s author was not disclosed.

Rachel Riley: 425-339-3465; rriley@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @rachel_m_riley.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.