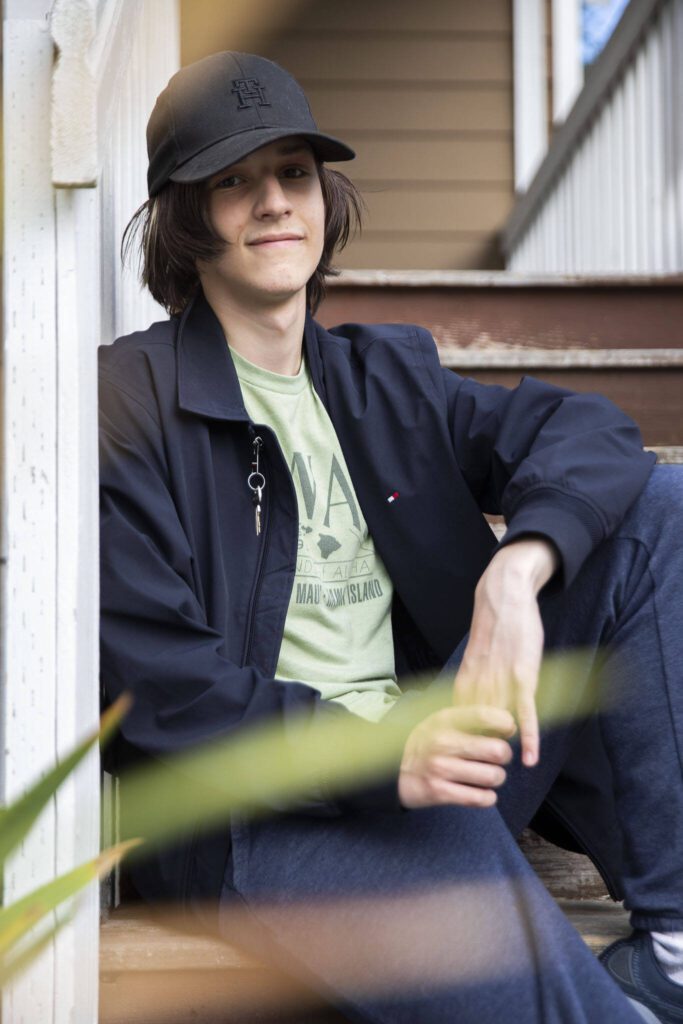

ARLINGTON — By the time Erica Knapp’s son turned 4, his respiratory system was already failing him.

Knapp’s son Vincent was in and out of emergency rooms every couple of weeks with severe asthma symptoms. He spent days in hospital Intensive Care Units.

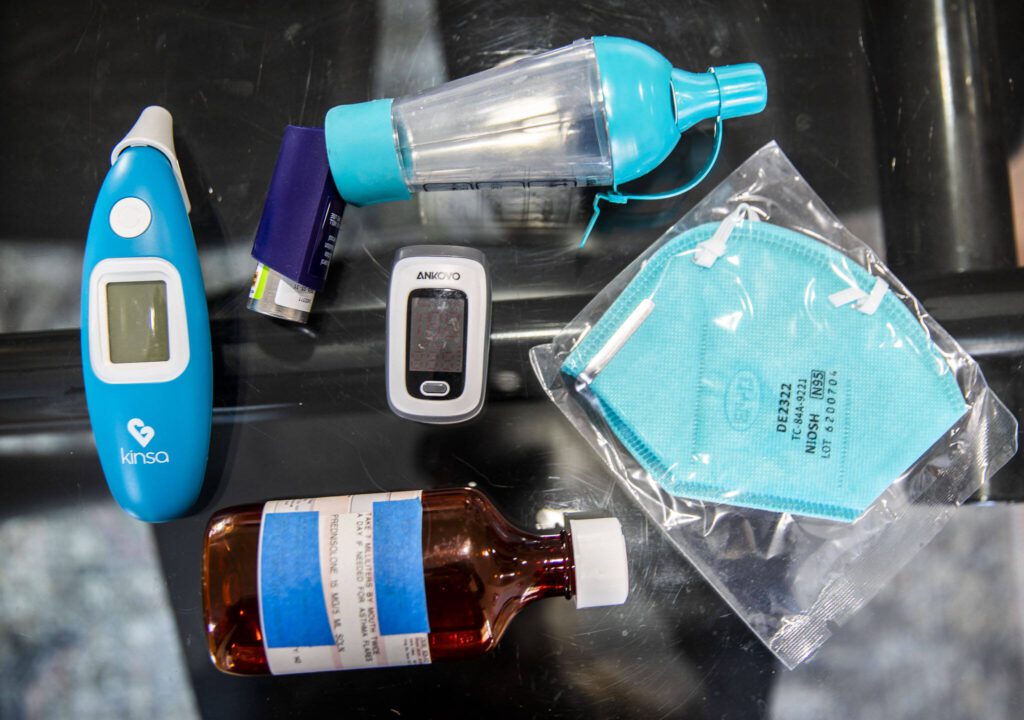

Doctors prescribed Vincent a litany of medications and an asthma care plan, and eventually, his health improved. Meanwhile, Knapp and her husband, Ryan, learned about the pollutants infiltrating their neighborhood near downtown Arlington and Arlington Municipal Airport.

For over a decade, Knapp has tried to manage the air pollutants that trigger her son’s asthma.

Each day, she checked the air quality. If it was poor, the family kept their doors and windows shut. They always had masks on hand. Knapp avoided taking her son downtown or to events like parades, she said, where big vehicles “spewed black smoke everywhere.”

Knapp’s family is one of thousands living in or near Washington’s ZIP codes most vulnerable to air pollution and the impacts of climate change including excessive heat, flooding and fires. Residents of these neighborhoods are often disproportionately low-income, minority and more likely to have health risks.

State and county agencies are working to help families like Knapp’s.

“I’ve tried to protect my child the best I can,” she said. “But there’s only so much I can do.”

‘It’s been eye opening’

Snohomish County is part of a strip of Western Washington — roughly from Everett to Tacoma — with high levels of air pollution including PM2.5, toxic particles smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

Vehicle emissions, wood and tobacco smoke, factories and construction work can all release these particles known to cause long-term respiratory damage. Residents in some polluted neighborhoods live an average of 2.4 years less than people living in other parts of Washington, according to a recent report from the state Department of Ecology.

Earlier this year, Snohomish County launched a Climate Vulnerability Tool to determine where environmental resources are most needed. The tool’s map shows clusters of vulnerable residents in many city downtowns, along I-5 and Highway 99 as well as in rural towns subject to wildfires and other wood smoke. Asthma rates, as well as other chronic illnesses, are often higher in these spots.

“It’s been eye opening for county and city staff to understand where the needs are the greatest,” said Eileen Canola, who works for the county’s Long Range Planning Division. “And how our past decisions for infrastructure have affected the lives and the health of our communities.”

Last year, a Pennsylvania-based study showed living in environmental justice neighborhoods — described as overwhelmingly poor and minority — increased the odds of having severe and uncontrolled asthma. Brandy Byrwa-Hill, a public health researcher who worked on the study, said these neighborhoods often overlapped with heavy traffic.

In 2021, Washington’s asthma prevalence was 10.5%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Arlington, two “blocks” on the county’s vulnerability map encompassing downtown and the airport show an asthma prevalence of 11.4%. In the county’s more affluent blocks with better air quality, like the coasts of Mukilteo and Edmonds, the map shows asthma rates at 9.9%.

At 12% or higher, the worst asthma rates in the county are blocks near busy highways in Marysville and Everett and in downtown Snohomish.

‘Hope of things changing’

Byrwa-Hill and Joel Kaufman, an epidemiologist who studies air pollution and respiratory health at the University of Washington, said it’s hard to know exactly why higher asthma rates overlap with these vulnerable blocks. It’s likely a combination of air quality, genetics and socio-economic factors, they said.

Residents living in these blocks are less likely to have jobs, transportation access or health insurance compared with those in other parts of the county. They’re also less likely to have the political power necessary to fight for better air quality, Kaufman said.

For years, Knapp’s family tried to move somewhere with fresher air and more health care resources, but they couldn’t afford it. It was hard just to keep up with their current mortgage along with Vincent’s doctor’s visits and medications — including an inhaler with a $200 copay.

“We put out so many offers, but kept getting outbid,” Knapp said. “It was difficult and defeating.”

Knapp said she’s asked Arlington officials about making rules like vehicle emissions requirements to improve air quality. She “didn’t get a lot of hope of things changing,” she said.

The city of Arlington declined to comment on its air quality or emissions requirements.

The state is requiring jurisdictions with 6,000 or more residents to develop new environmental health plans by 2029. But combating pollution and climate change is a task too big for a city or town to tackle alone, said Molly Beeman, the county’s energy and sustainability manager.

Snohomish County is ahead of schedule with its climate plan. Part of the plan is partnering with smaller jurisdictions that have low-income or otherwise disadvantaged populations on solar, emissions reduction and other environmental projects.

‘What we can reverse’

Statewide, the Department of Ecology is working to install at least 50 air quality monitors in 16 “overburdened” neighborhoods by the end of the year. In June, the department installed one outside Fairmount Elementary School in Everett, where students suffered health problems after a mining company began digging up gravel just feet away from the school.

Right now, the state is accepting applications for a total of $10 million in grants to support local air quality projects. The deadline is Oct. 24.

This work is part of the state’s Climate Commitment Act legislators passed in 2021. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 95% by 2050, the state launched a cap-and-invest program that limits carbon emissions statewide. So far, the state has garnered more than $2 billion by requiring businesses to pay up for their emissions. The state allocates 35% of this revenue to environmental health projects in “overburdened communities” and at least 10% to tribes.

Conservatives in Washington have criticized the act as leading to increased gas prices and other costs. Next month, voters will have the chance to repeal the law with Initiative 2117. The repeal would jeopardize the state’s air quality sensors and other environmental projects, said Kate Miller, a state air monitoring specialist.

Tackling air pollution is important because it is a “reversible” asthma risk, said Catherine Karr, a pediatrician and researcher who works to educate vulnerable Washingtonians about environmental health.

“You can’t change genetics, but we might be able to change a child’s experience of air pollution,” she said. “And maybe, by taking away what we can reverse, those things won’t tip them over the edge into developing the disease.”

Vincent, now 15, has a more mature respiratory system and doesn’t have as many bad asthma days. Still, he carries his inhaler and often wears a mask to school. Knapp still checks the state’s air quality monitor daily.

Former Herald writer Ta’Leah Van Sistine contributed to this report.

Sydney Jackson: 425-339-3430; sydney.jackson@heraldnet.com; X: @_sydneyajackson.

What you can do

To mitigate air pollution exposure:

• Stay indoors and keep windows closed during heavy traffic hours;

• Use indoor air purifiers and filters (The Puget Sound Clean Air Agency website has DIY air filter instructions);

• Update vehicle air filters regularly;

• Avoid tobacco smoke; and

• Replace non-EPA certified wood burning stoves.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.